What is this drought? What is a "meteorological drought" and how is it affecting the country? And in Lisbon, why aren't we feeling the drought?

Walking or cycling along the river, the Tagus estuary is as magnificent as ever. Sometimes the low tide reveals a little more of the riverbank, but a few hours later we have water all the way to the "tip" of the city. In the gardens, the lawns are being watered, keeping them green. In Lisbon, everything seems to be normal - the continuous sunny days warm us up in a winter that is still cold. These days feel good and distract us from the reality of the country, experiencing one of the most serious droughts in recent years.

Those who walk or cycle in the city end up having a greater perception of the weather around them. After all, the weather ends up mattering more, having an impact on the clothes you wear that day or even on your transportation options - a rainy day usually results in a lower modal share for cycling, for example. So anyone who usually walks or cycles in Lisbon will have noticed how little it has rained.

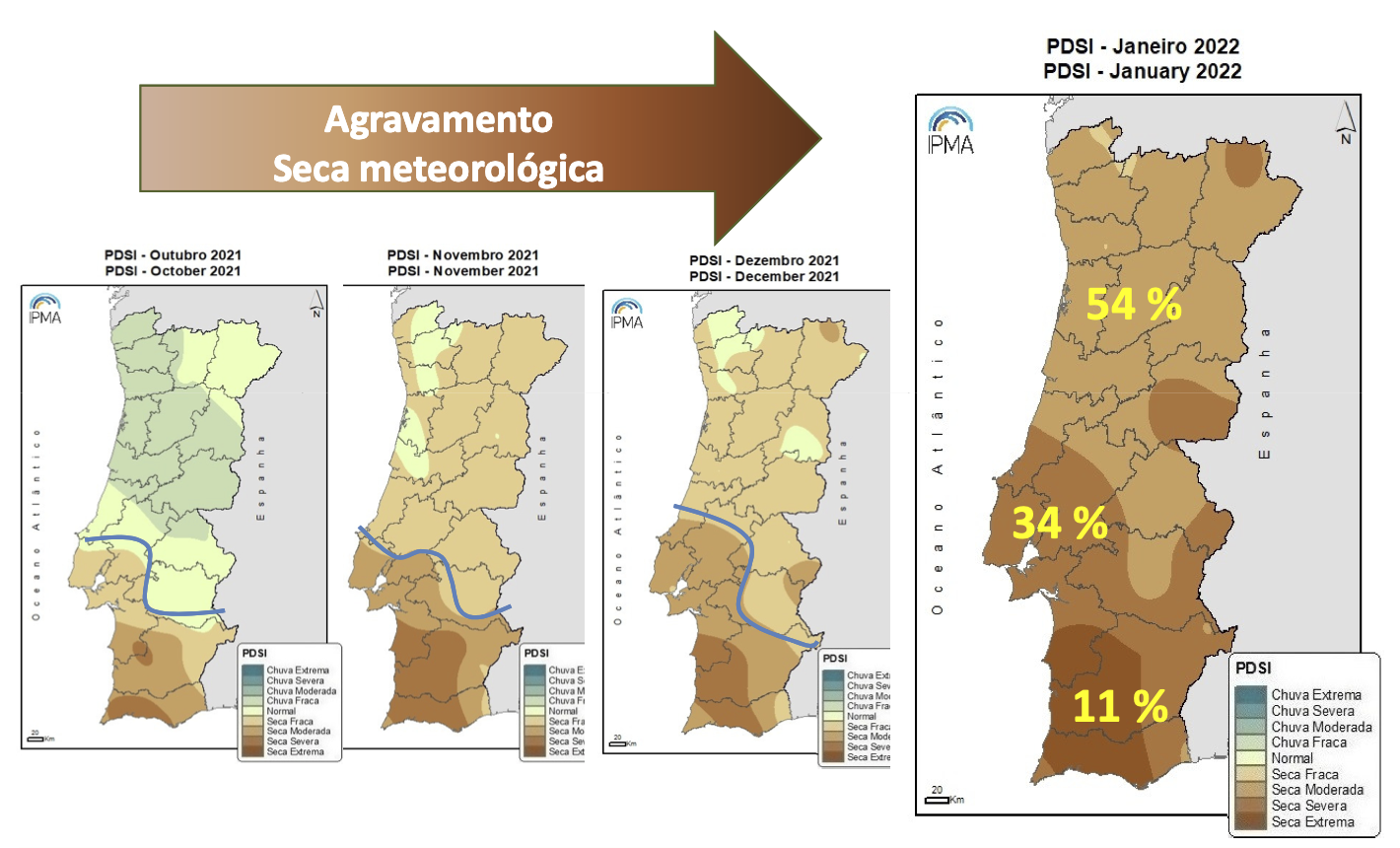

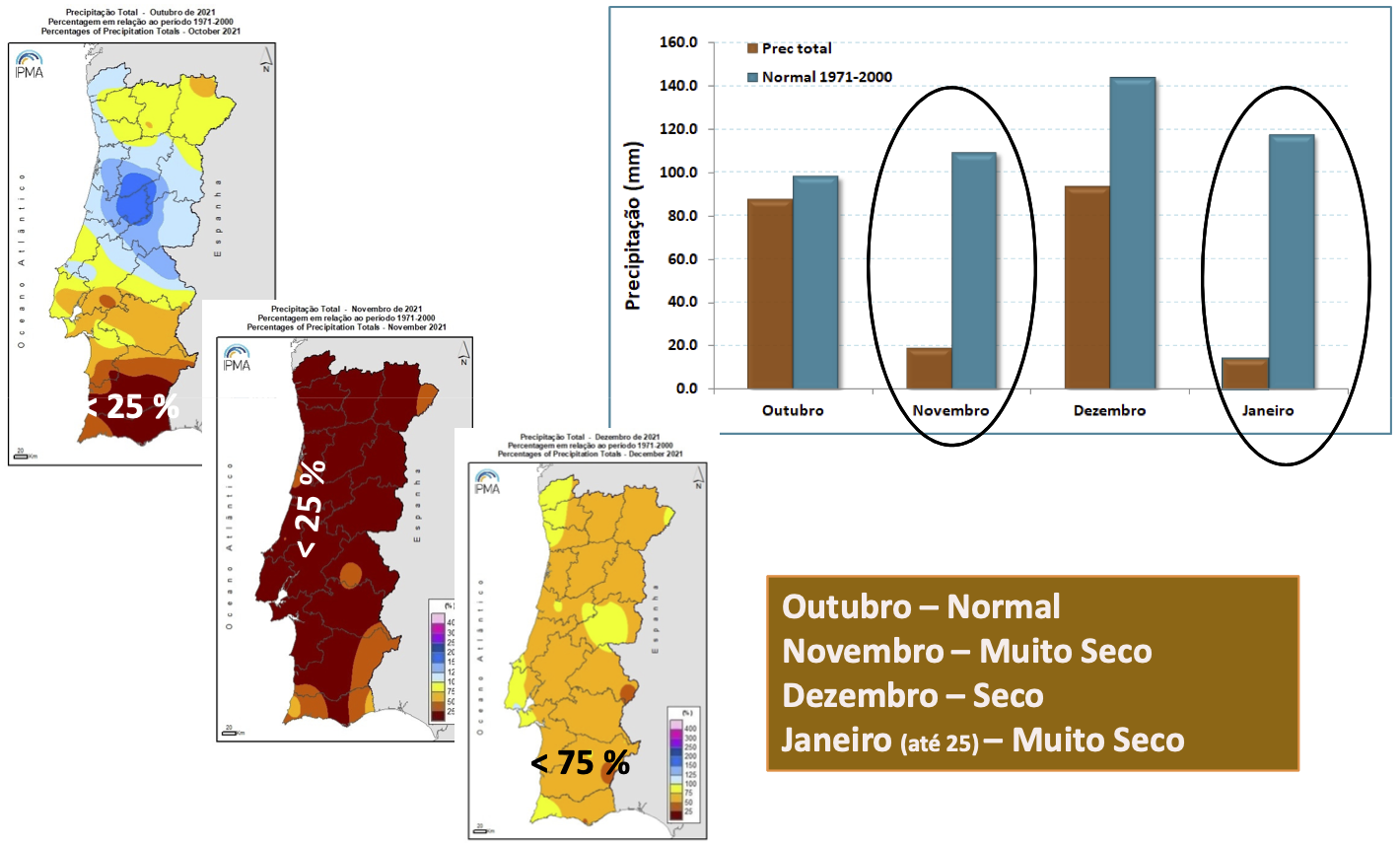

My memory will tell me that last fall was dry and, apart from a week or two at the end of December, it rained little or not at all. Data from the Portuguese Institute of Meteorology and Atmosphere (IPMA) confirms this: "The meteorological drought that began throughout the territory in November 2021 continues and worsened on January 25, 2022 in mainland Portugal. Compared to December, there was a significant increase in the area and intensity of the drought situation, with the entire territory in drought, with 1% in weak drought, 54% in moderate drought, 34% in severe drought and 11% in extreme drought."

Meteorological drought, what is it?

The IPMA talks about "meteorological drought", so in order to understand the scenario the country is going through, it is important to look at this concept. According to the IPMA itself, drought is distinguished according to what it affects, and there can be a meteorological droughta agricultural droughta hydrological drought and a socio-economic drought. We talk about a socio-economic drought if people lack water, i.e. if there is more demand for water resources than there is supply to provide people. Agricultural drought occurs when there is a lack of water available in the soil to meet agricultural needs. Hydrological drought, on the other hand, refers to the reduction of average water levels in reservoirs and consequently in the soil, and occurs after a long period of precipitation deficit.

The meteorological drought is the result of less rainfall than usual and may not be nationwide - This is because the atmospheric conditions that result in precipitation deficiencies can be very different from region to region. The worsening of meteorological droughts can lead to water shortages for agriculture, reservoirs and populations, in other words, it can lead to the other types of drought mentioned above. Meteorological drought in itself means a "precipitation deficit"which, if it continues over time, "It will cause water deficits in the soil, in reservoirs and could affect populations." explains Vanda Cabrinha, a meteorologist at IPMA. For the time being, this is not the situation the country is in and IPMA is still hopeful that there will be rainy weeks or months ahead that will at least alleviate the situation.

What is at stake today?

At the moment, the meteorological drought is affecting the entire continental territory of our country: 11% is in extreme drought, 34% in severe drought, 54% in moderate drought and only 1% in weak drought, according to IPMA data from January 25th. To find a more severe drought than this one, we have to go back 17 years, to January 2005When 22% of the territory was in extreme drought, 53% in severe drought and 25% in moderate drought.

The reason for this drought is the low rainfall recorded in recent months, particularly in November and January. In fact, last January was the sixth driest since 1931 and the second driest since 2000, after that January 2005, according to IPMA. It rained very little - only 12% of the normal amount - which has consequences for the amount of water in the soil, which has decreased significantly compared to the end of December throughout mainland Portugal. In the north-east and south of the country, there is only 20% of the water that could be expected in the soil and in many places in these regions, plants can no longer draw water from the soil. The average amount of rainfall was 13.9 mm in January; in 75 % of the territory the amount of rainfall was even less than 10 mm - was the case in Lisbon, where the total rainfall was only 5.5 mmIn other words, what usually rains in the dry months of July and August (we're already there).

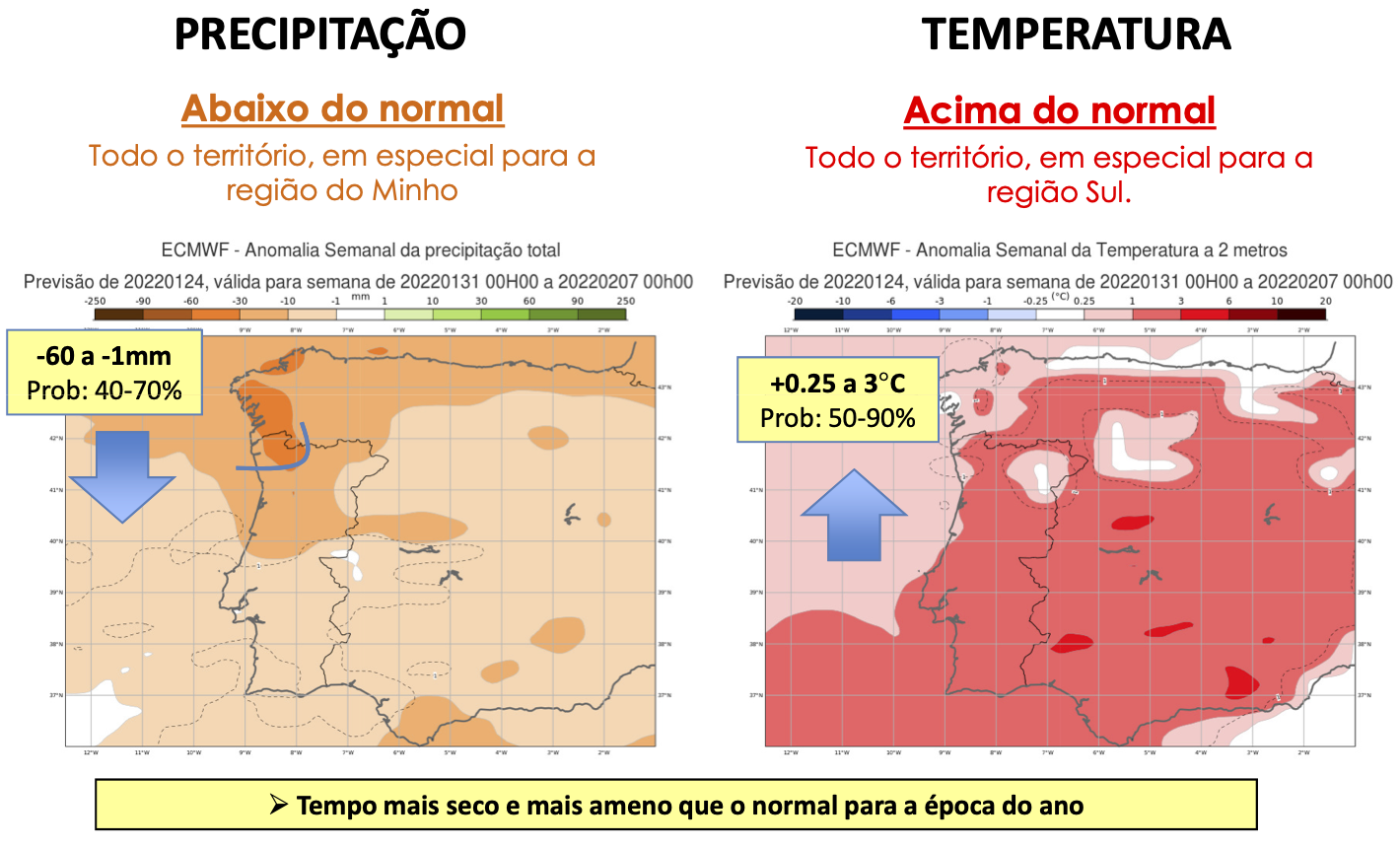

Last January was also the fifth warmest January since 2000with an average air temperature of 9.65 °C - 0.84 °C higher than normal. Only January 2016 was warmer, with 10.78 ºC. The maximum air temperature was the highest in the last 90 years, with an average value of 15.29 °C, 2.20 °C more than the normal value. The average minimum air temperature was 4.02 °C, 0.52 °C lower than the normal value. (Note: the normal value is based on the period 1971-2000.)

February promises to continue to be dry and even hotter, so the meteorological drought is expected to worsen. "For the drought situation to decrease significantly or even cease in the month of February, it would be necessary for there to be more than 200/250 mm of rainfall in the North and Center and more than 150 mm in the South, a situation that only occurs in 20% of the years."writes the IPMA. In Portugal, for meteorologists, the hydrological year starts on October 1st and ends on September 30th, i.e. it starts when water reserves generally reach their minimum and the rainy season begins. Considering the current hydrological year up to January 25, the accumulated rainfall shows a deficit of -255 mmIn other words, it rained 45% less than normal.

How does Lisbon want to adapt?

In big cities like Lisbon, the drought is not felt directly. The Tagus estuary that bathes the capital is still full of water, gardens continue to be watered and there is no shortage of water in the taps. But "the first impact" in a metropolis like Lisbon, says Vanda, it can be "in the price of meat, food and water itself". "There will be no shortage of water" - at least in light of the current scenario, but the drought may have "an economic cost". "There is an increasing likelihood of more droughts and longer droughts, and this could affect populations in large cities in the long term"warns the expert.

That's why it's urgent for cities to adapt. More than three quarters of European citizens live in urban areas and their family, social and economic activities depend on access to water. Around a fifth of the total volume of fresh water abstracted in Europe feeds public water supply systems - water for households, small businesses, hotels, offices, hospitals, schools and some industries.

For now, Lisbon is completing its Climate Action Plan (CAP), a document that outlines the city's response to climate change, including the increased likelihood of droughts, over an eight-year horizon - until 2030. The Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML) also has a climate crisis response plan - the Metropolitan Climate Change Adaptation Plan (PMAAC-AML), created in 2019. And at national level, there is a Drought Prevention, Monitoring and Contingency Plan.

Vanda regrets that the country's responses to the drought are still "very much on paper, with predetermined measures to act"There are "still regionally difficult to apply these guidelines". Some of these answers would be simple: optimize irrigation for morning or evening schedules, in which the water that ends up evaporating in the process is reduced as much as possible; avoid placing lawns on traffic circles or other areas without human use, opting for dry meadows that live with the seasons and don't need artificial irrigation; or avoid merely decorative water features that only promote water waste rather than its reuse.

A preliminary version of the PAC, which was in public consultation last year, states that "between the climate changes projected for Lisbon by the end of the century"a "decrease in average annual rainfall, which is expected to worsen droughts and water shortages". In the Portuguese capital, it rains an average of 743 mm per year, with the wettest months being November and December with figures of over 115 mm/month. July and August are the driest months, with monthly figures in the order of 4 and 6 mm - however, it should be noted that this January 2022 was as dry in Lisbon as a typical summer month. On average, there are only 24 days a year with rainfall greater than or equal to 10 mm. In other words, Lisbon has already had little rain and it is expected that it will continue to rain less and that there will be more situations of drought and water scarcity.

In the PAC, Lisbon stipulates "a set of quantifiable targets for minimizing the impacts associated with the main climate changes projected for Lisbon"including a decrease in rainfall. The city will need to bet "the efficiency and sustainable management of water resources, as well as regulating the water cycle in urban areas and improving the rainwater drainage system". Looking at concrete measures, By 2030, Lisbon aims to reduce its drinking water consumption by 30% (compared to 2018) and create 30 hectares of new biodiverse rainfed grassland. These meadow areas are natural ecosystems that manage themselves according to water cycles - green in winter, after the first rains; orange in summer. The 30 new hectares of dry meadow mean a 10-fold increase in this type of area in the city; and 20% of these 30 new hectares will result from the reversal of currently irrigated water.

Lisbon will also seek to increase soil permeabilityThis can be done, for example, by opting for sidewalks that allow water to seep underground or by increasing the number of green spaces in the city (by 2030, 25% of Lisbon should be green areas). In fact, the municipality sees its green infrastructure as a "fundamental tool for climate adaptation" and will be looking for "natural-based solutions", such as the aforementioned dryland meadows, but also the creation of open-air water retention basins that allow water to seep into the ground. "better management of the water cycle by promoting water retention and infiltration" on rainy days.

At metropolitan level, the measures are not very different. AML plans to increase the resilience of natural and agroforestry systems to water scarcity by restoring riverside vegetation, optimizing the water available for agricultural irrigation, promoting small dams and ponds for farmers to use, or promoting collective cultivation. The aim is also to increase efficiency in the distribution and consumption of water by implementing a metropolitan drought management plan, monitoring and correcting water losses in distribution systems, promoting water efficiency in green spaces and urban environments, raising awareness among the population about saving this resource, or investing in the reuse of wastewater instead of sending it straight to the sewer. Finally, the metropolitan plan provides for better management of water resources, with data monitoring, increased storage capacity, the creation of more permeable surfaces in urban areas, and better monitoring and licensing of water abstraction and polluting discharges.

The drought we are experiencing today is not unprecedented. Droughts have been frequent in mainland Portugal for several years, mainly affecting the regions south of the Tagus, with severe consequences for agriculture and livestock. Drought is considered a natural disaster which, unlike others, acts slowly and silently and may not have an immediate impact on human life. However, if this drought continues, as we saw earlier, it can affect entire populations for a long time. Droughts cannot be avoided, but they can be minimized with an adequate response, starting with the cities.

As has also been mentioned, the drought doesn't affect the whole country equally. While this problem may be less felt in Lisbon, it is not the same in Setúbal, for example. This AML municipality, located south of the Tagus, was one of the worst affected by droughts between 2000 and 2020, according to IPMA data collected by Público. Vanda Cabrinha explains "structural problems" of the region, "at the level of dams and other reservoirs"leading to a "structural water deficit". While the inland area south of the Tagus is currently served by the Alqueva, the same is not true for the coast between the Setúbal Peninsula and the Alentejo Coast. In the middle of February and at the end of the month, IPMA will issue new drought situation reports.