Chronicle.

Lisbon's toilets have been destroyed. Erected in strategic places such as squares, gardens and public transport stations with the commercialization of public space, we normalized their disappearance.

Lisbon's toilets have been destroyed. Erected in strategic places such as squares, gardens and public transport stations, with the commercialization of public space, we normalized their disappearance. Some of the ones that still survive are as if they no longer existed. Because they are in poor condition, with closed doors and reduced opening hours (by the time we leave work and can go outside to socialize, they are already closed). Other toilets that have survived are public works from the 20th century. They are made of brick, stone and cement. They are not containers. These toilets were built as a concern and not as a nonchalance. They were free and not paid for (no one should have to pay to go to the toilet, it's a basic necessity).

Lisbon smells of piss. And they blame us for it.

A city having toilets for its citizens is no less important than having functioning garbage collection, proper street lighting, playgrounds, sewers, fountains, sidewalk repair, libraries... Providing public toilets should not be seen as a luxury or a charity, but as a necessity and an obligation. All the free public toilets that still exist, and which have resisted closure, represent the city's recognition of its duty to make this infrastructure available to its citizens. Toilets are also used for washing our hands or drinking water. And it's healthy to drink the water you want without self-policing for fear of not finding another toilet afterwards (holding in urine can increase the risk of a urinary infection and kidney problems, as urine is responsible for expelling batteries and impurities from our bodies).

There is a disparity in the number of toilets between parishes. For example, even counting the number of inhabitants and square area, the parish of Arroios has many more public toilets than the parish of Penha de França. Those who work in some of these toilets are not valued or respected. There are cleaners who have been working for the Juntas de Freguesia for over 10 years on green cards (no social security, no work accident insurance, no vacation pay). In fact, these people are very important for the city to function.

The case of inaugurations

The inauguration of public toilets is over. Gone are the days when they were built as public works, as a concern, as a common good. Today, in addition to neglecting the ones that the 20th century left us - by not maintaining them or destroying them - we have built very few and the ones we do build are paid-for containers, almost always broken and small, and therefore not inclusive. They used to be made of brick, stone and cement, not containers. Before they were made to last and not to be temporary things. They used to be free and not paid for. We need to open more toilets in the public space and, before that, perhaps take good care of the ones we still have.

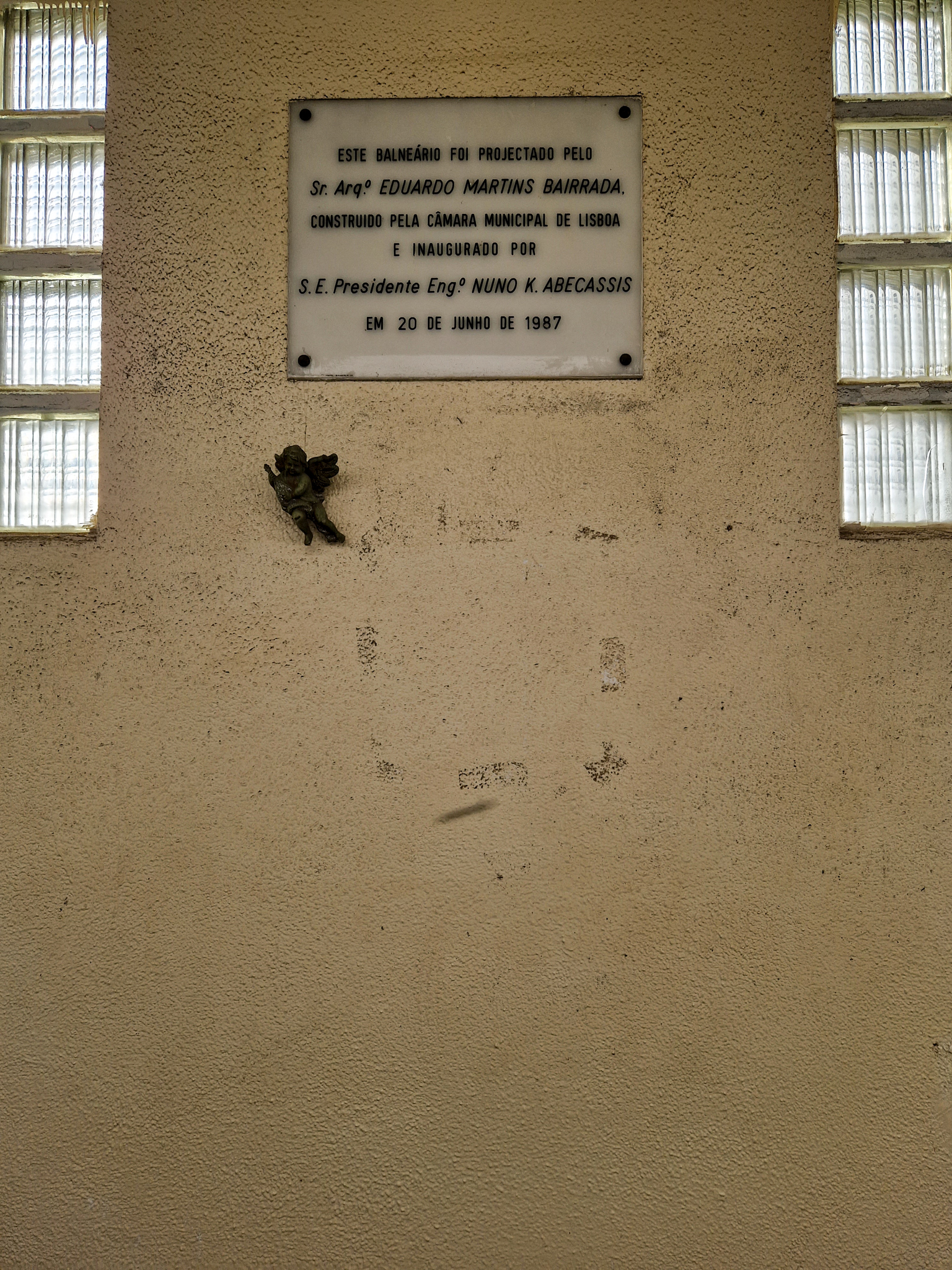

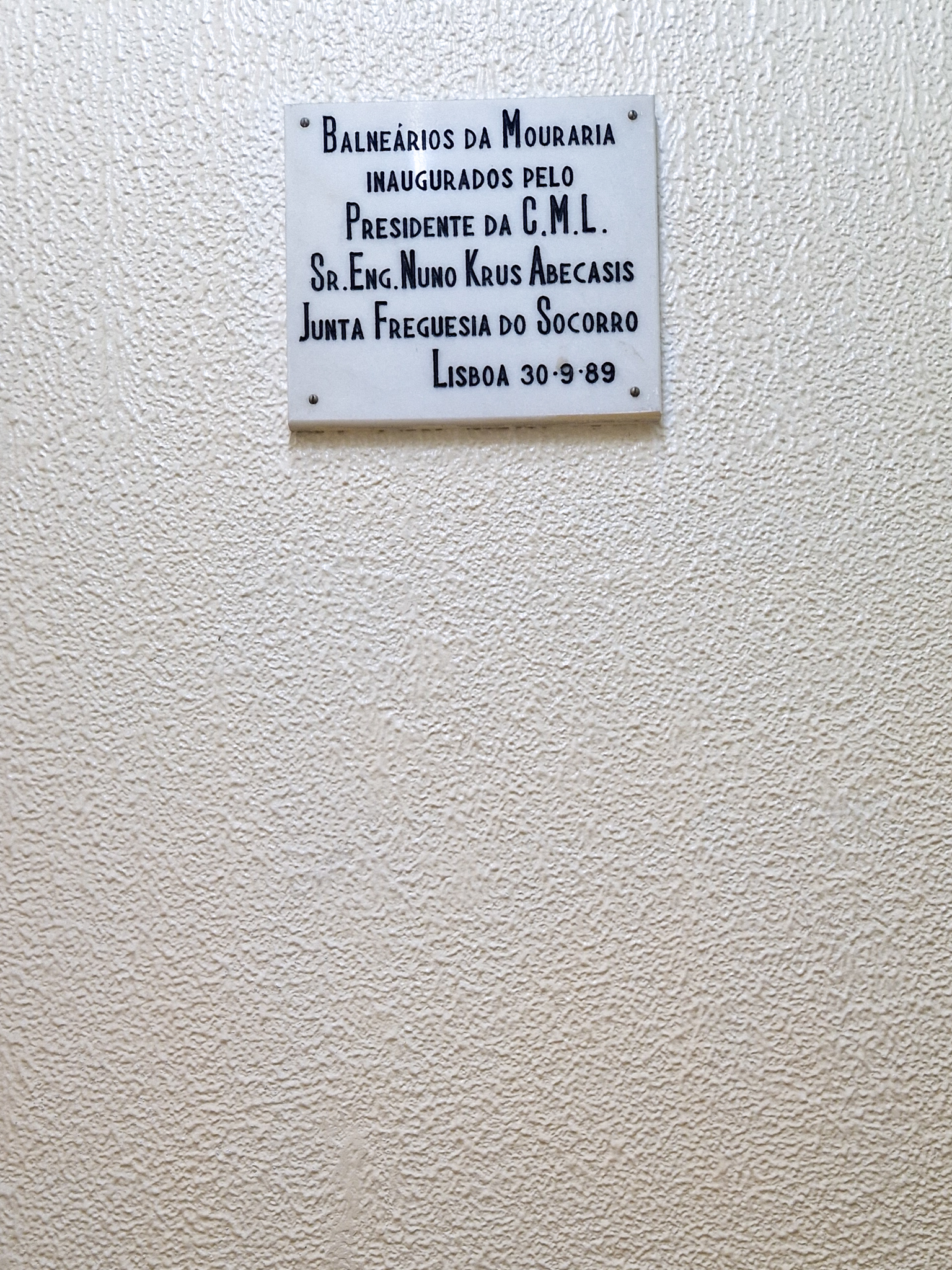

Two examples of public toilets made like real works, of brick and mortar, built like a house - a bathroom - and not a container:

WC in a garden in Belém, Lisbon

Plaque for the inauguration of a bathhouse in São João da Praça, Sé, Lisbon, in 1987

A toilet/bus stop in Sintra

Inauguration plaque for a bathhouse in Mouraria in 1989

The case of taxi drivers

In the photo on the left, a taxi driver in Martim Moniz is showing his white plastic card, which gives him free access to the toilets in paid containers.

Martim Moniz, a square that is also a cab rank, has no toilets. Many taxi drivers have a plastic bottle in their car for urinating. Many taxi drivers have this card. Many taxi drivers don't know they can have this card. Several taxi drivers know they can have this card but don't want to because they say they prefer to use the toilets in cafés because the public ones are often dirty. The example of taxi drivers is used to talk about something much bigger: where all the other workers without a fixed office go to the toilets, such as letter carriers, parish council night clerks, food delivery couriers, etc. This white card - a fight by taxi drivers for the right to free toilets - continues to be the fight of us all. This card is a tragedy, because it normalizes everyone's right as belonging to just a few.

The case of non-solutions

Not only did they take away our right to go to the toilet, but they also banned us from using the street as a toilet. When public toilets began to disappear, of course the need for people to go to the toilet didn't disappear. Cafés, restaurants and other commercial establishments have started locking their toilets or installing access codes, like McDonald's and Starbucks, or sticking papers on the door saying "customers only".

When the parish councils stop providing us with this service and the stores also become a barrier, there is only one option left, and that is the street, but even this has been harassed - in 2016, the Misericórdia parish council started putting expensive paint on walls in Lisbon that projects urine onto those who urinate. Other councils have done the same. It's sad when a municipality thinks it can solve this problem by making it harder to urinate on walls and not creating a network of public toilets for its residents and visitors. Sometimes there are toilets, but they have timetables. When they're closed, where can we go to the bathroom? The right to pee is threatened.

The case of conditions

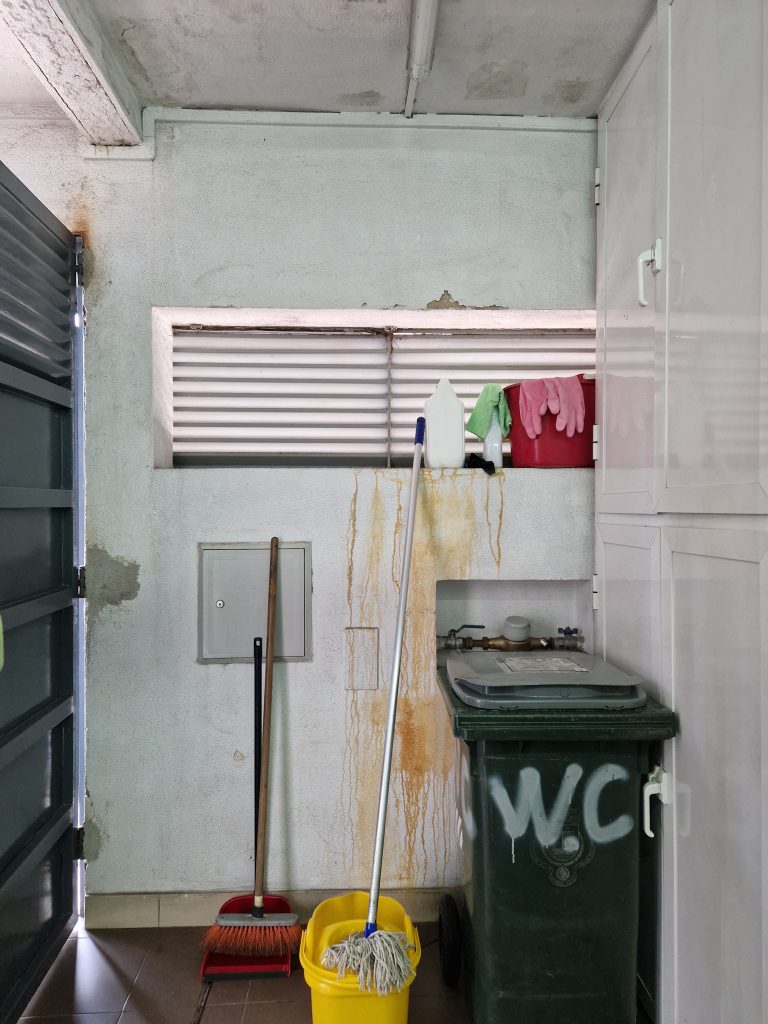

It's not just about opening a public toilet. Public toilets need maintenance, and when this isn't done, things get damaged, which is an excuse to close everything down.

Where does the money for toilets that Lisbon City Council gives to the parish councils as part of the decentralization of competences actually go if the infrastructure is in such poor condition? With broken cisterns, broken dryers and benches, fallen ceilings, broken lights, moldy walls, the smell of sewage, rain coming in, stairlifts that don't work. As we've seen so many times on our visits. And we often think that the toilets aren't clean when, in fact, they are more than clean. What's needed is work that doesn't depend on the cleaning staff. We're sharing some of the images we took.

Mould

The case of the gates

It wasn't like that before.

We shouldn't have to pay to go to the toilet. It's a basic need. It's part of the right to citizenship. We are already taxpayers. We can't normalize paying when these same toilets have never been paid for.

The Cais do Sodré train station has always had free toilets, but a few years ago they started paying for them. The public toilet at Largo do Carmo has always been free, but two months ago they installed gates. On the website of the Penha de França Parish Council, a free toilet was announced in 2021, but now it's paid for. The toilet at the Cais do Sodré river terminal is free for children up to the age of six, but if your child is seven you pay.

Why is it that some parishes within their own parish have some public toilets that are paid for and others that are free? Or why are there parishes with free public toilets and other parishes where they are paid for? The public toilets that are paid for and run by the parish councils don't give receipts, so the question is: where does this undeclared money go? At the moment, parish councils have complete freedom to decide what they want with regard to their public toilets, but this should be regularized.

Free for children under 6

These are just a few examples, but there are many more. What we need to understand is that this wasn't the case. That's why we can't normalize having to pay to go to the bathroom - a right. Gates are a very aggressive element, not to mention the fact that wheelchairs can't get through.

In 1963, a law in the UK declared that the use of gates in public toilets would become illegal and that all local authorities had six months to remove them: "All existing turnstiles in any part of a public toilet or public sanitary facility controlled or managed by a local authority, or at any entrance to or exit from a public toilet or public sanitary facility, shall be removed no later than six months after the passing of this Act; and after the passing of this Act, no turnstile shall be installed at any entrance to or exit from a public toilet or public sanitary facility." With legislation, we may be able to change the way councils and the City Council deal with Lisbon's public toilets.

The case of disappear

The public toilets we used to have have have been quietly disappearing over time. Those who knew them recognize their absence. Those who haven't seen them open may think that the city has never guaranteed this service to its citizens and that what is happening is normal.

What is happening is not at all normal.

The toilet in Rossio Square no longer exists. The one in Praça do Comércio is also gone.

The toilet in the Camilo Castelo Branco Garden, in the parish of Santo António, is no longer a toilet but an events room. The toilet in the Alameda garden used to be on both sides, but now it's only on one because the other is now used as a storage room for the Penha de França parish council. The toilet at Antero Quental is closed. The toilet in Jardim Cesário Verde, in Arroios, has been covered up. The WC/kiosk designed in the Roque Gameiro Garden, in Cais do Sodré, is not used as a toilet but as a Carris ticket office (the "WC Kiosks" project was presented to the Lisbon City Council in 1913, by the architect José Alexandre Soares; on the architectural plan, he writes: "project for toilets with annexes for the sale of flowers and newspapers, intended for public squares and gardens").

And, unfortunately, there are many other examples.

The case of the Metro

Lisbon's Metro stations once had toilets. Many of those that used to be public are now only for employees and shopkeepers (one of many examples might be the Martim Moniz station).

WC São Sebastião station

''Toilet facilities temporarily closed''

Airport station toilets

Off-duty payment system

WC Marquês Pombal station

WC for employees/tenants only

WC Campo Grande station

''Toilet facilities temporarily closed''

We are clients of the Lisbon Metro. It's them - the company - who call us this. We're customers because we pay for transportation, but they still don't give us access to the toilet service. When we go to eat sardines at the tasca as customers we have the right to use the toilet and we don't pay an extra 30 cents for that, but with the Metro it's different. In fact, in the Metro we don't even pay that now because all the toilets that the Metro said were open are now closed.

In 2018, two Metro de Lisboa press releases issued a document saying:

''Following the opening of the toilets at Campo Grande station, which met demand expectations, the next phase of the project is now being implemented, covering a further fourteen stations, in particular the interventions and adaptation works underway at Aeroporto, Alameda, Marquês de Pombal and Saldanha stations, which are scheduled to open during the first half of 2018, with the remaining facilities expected to be gradually made available by the end of 2018, for a total of 15 new facilities."

"After the opening of the toilets at Campo Grande, Aeroporto and Marquês de Pombal stations, there will now be another toilet at São Sebastião station on the Blue Line.“

All these toilets are closed with a sign on the door saying "toilet facilities temporarily closed". And of course "temporarily" It's very relative, because we've been seeing them closed for at least two years now. The story of the lack of toilets in Metro stations also applies to other types of stations: bus, boat and train.

The case of the protest

We are @infraestruturapublicaWe were a group of people protesting for more public infrastructure. At the end of January, we took to the streets for a week with a portable toilet, a public toilet built by us. citizens. In squares, gardens and even stations we did voluntary public service - the public service that the councils and the City Hall aren't doing.

On the 23rd, we went to Paiva Couceiro Squarein Penha de França. The toilet in this square belongs to the Penha de França Parish Council, which, in 2021, wrote that it was a free toilet. Now it's 2024 and I'm paying for it. Paiva Couceiro is a square full of tables and chairs where people read newspapers, play cards, have lunch, chat, relax. Etc. Many people who use the square have told us that the toilet, a container, is there but that it's often out of order; that it doesn't give change; that you insert the coin but the machine eats it without opening the door; that they're already old and therefore have bladder problems that require them to go to the toilet more often; that their friends who play cards in Alameda don't pay to go to the toilet, but that there, in Paiva Couceiro, they do; that they drink less water throughout the day so they don't have to go to the toilet so often; that some of their friends have already gotten stuck there and it took the parish hours to get a technician to get them out; that because of all this they have to go many times pee e poop behind the trees in the square.

On the 24th, we went to the Alameda garden. Our bathroom was in front of the garden's official public toilet. We arrived at three in the afternoon and the toilet was already closed. The time sheet said it was open until 4 p.m. A lady came to tell us that they had even closed two hours before that. These council toilets don't close at the times they say they do. Officially they close early, but in reality they close much earlier. Many days they don't even open. It was a sunny day and the fountain and garden were full of people. When people realized that the council's toilets were already closed, they came to use ours. Lots of people came.

On the 25th, we went to the Martim Moniz Square which doesn't have a public toilet. The Martim Moniz Metro station used to have a public toilet, but now it's only for shopkeepers and Metro employees. Many people came to use our toilet. Many people also came just to wash their hands or just to drink water because the Martim Moniz drinking fountain wasn't working (it's been out of water for some time). A cab driver came from the cab rank to use the quick toilet and get back to work (all his colleagues are angry with the Santa Maria Maior parish council for not giving them a toilet). We also saw a large pit made in the soil of the square's flowerbeds - which is the "official" everyday toilet for those who use the square. It's almost criminal that the Junta doesn't install a toilet there. It's such a central area, so heavily used and increasingly full of homeless people. It's an attack on public hygiene and our most basic rights.

On the 26th, we went to the Praça do Comércio. Our toilet is above the public toilet that used to be there, which closed many years ago. The municipal police say they always have to go to the toilet in a Pingo Doce, because there's no solution in that square.

On the 27th, we went to the Rossio square. Our toilet was also above the underground public toilet that used to be there and closed many years ago. Some people who passed us still remembered what was there before. The florists in the square showed us the bucket in which they make peeand then lie down in the gutter in front of the kiosk. They're upset that there's no toilet in the square to serve their physiological needs.

On the 28th, we went to the public toilet in front of the Largo de Santa Bárbara. It's a good toilet, free and clean, but on weekends it ends at 5pm. We went on a Sunday and were there from 5pm to 10pm. The opening hours of this facility need to be extended.

On the 29th, we went to Cais do Sodré station. Our bathroom was in front of the toilets, which are paid for and have gates. It wasn't that long ago that you started paying to go to the toilet. Now it's 50 cents. Many people didn't put any money in and went to our toilets for zero euros - just like before. Many were upset that they already paid for tickets and public transport passes and yet still had to pay to go to the toilet. It should be an obligation for train, metro and boat stations to give us this service.

With this protest, we wanted to demand toilets that are not associated with consumer spaces. The toilets in cafés, which don't lock them, provide a public service. They are the service that the councils, who are responsible for public toilets, don't give us. The lack of this infrastructure in our daily lives is a problem of health, equality and circulation. Toilets make public spaces not just a place to pass through, but a place to be. They are democratic urban facilities.

Public toilets are also a gender issue. A story to finish: at the end of the 21st century, just after the invention of the flush toilet, the London Women's Sanitary Association began campaigning with lectures and pamphlets on the subject of public toilets. It was only later, after the First World War had ended, that toilets for women began to become commonplace. There were more urinals than toilets for women on the streets. Men were bodies that moved in the street, such as to go to work, while women being in public space was considered inappropriate. This patriarchal society tried to control the movements women by not providing them with public toilets. The appearance of these toilets represented the gradual opening up of new leisure and work opportunities previously unavailable to women. The issue of toilets became a feminist cause - "women felt restricted in their movements because of the lack of toilets. Bound by this urinary leash". This "urinary leash" is unfortunately still present in our daily lives - in the daily lives of all of us.