The 3-30-300 rule says what anyone should be able to see from their home window and have around them so that the place where they live is heat-resistant. How does it apply to Lisbon?

How many trees can you see from your window? What percentage of your area is green? How far are you from the nearest park? These are the questions we should ask ourselves when we want to check the 3-30-300 rule.

But what is this rule?

According to Cecil Konijnendijk, co-founder of the Nature Based Solutions Institute (NBSI) and honorary professor at the University of British Columbia in the areas of green space governance, afforestation and urban ecology, anyone should be able to see at least three trees from their window, live in a neighborhood with at least 30% of green cover (gardens, parks, etc.) and be within 300 meters of a green space.

This is precisely what we are investigating in this article. How many buildings in Lisbon comply with this rule? Is there any relationship between the heat island effect and the buildings that don't comply with this simple rule? Where are they located? What effects can extreme heat have on our lives?

The 3-30-300 in Lisbon

The 3-30-300 rule is basically a good tool for analyzing and comparing asymmetries in the distribution of green spaces. It also gives us a better understanding of the place where we live, which makes it possible to prioritize interventions in the collective space and act to protect people from the effects of heat islands, using natural air conditioning in Lisbon's collective urban space.

See how this rule applies to the building you live in:

To calculate the 3-30-300 rule, we analyzed, for each building in the municipality of Lisbon:

- if there are at least 3 trees within a radius of 50 meters;

- if the green coverage area of the territorial section corresponds to at least 30%;

- if is there a garden within 300 meters and, if so, which one?.

Criterion by criterion analysis

This is the scenario in Lisbon for each of the layers under analysis:

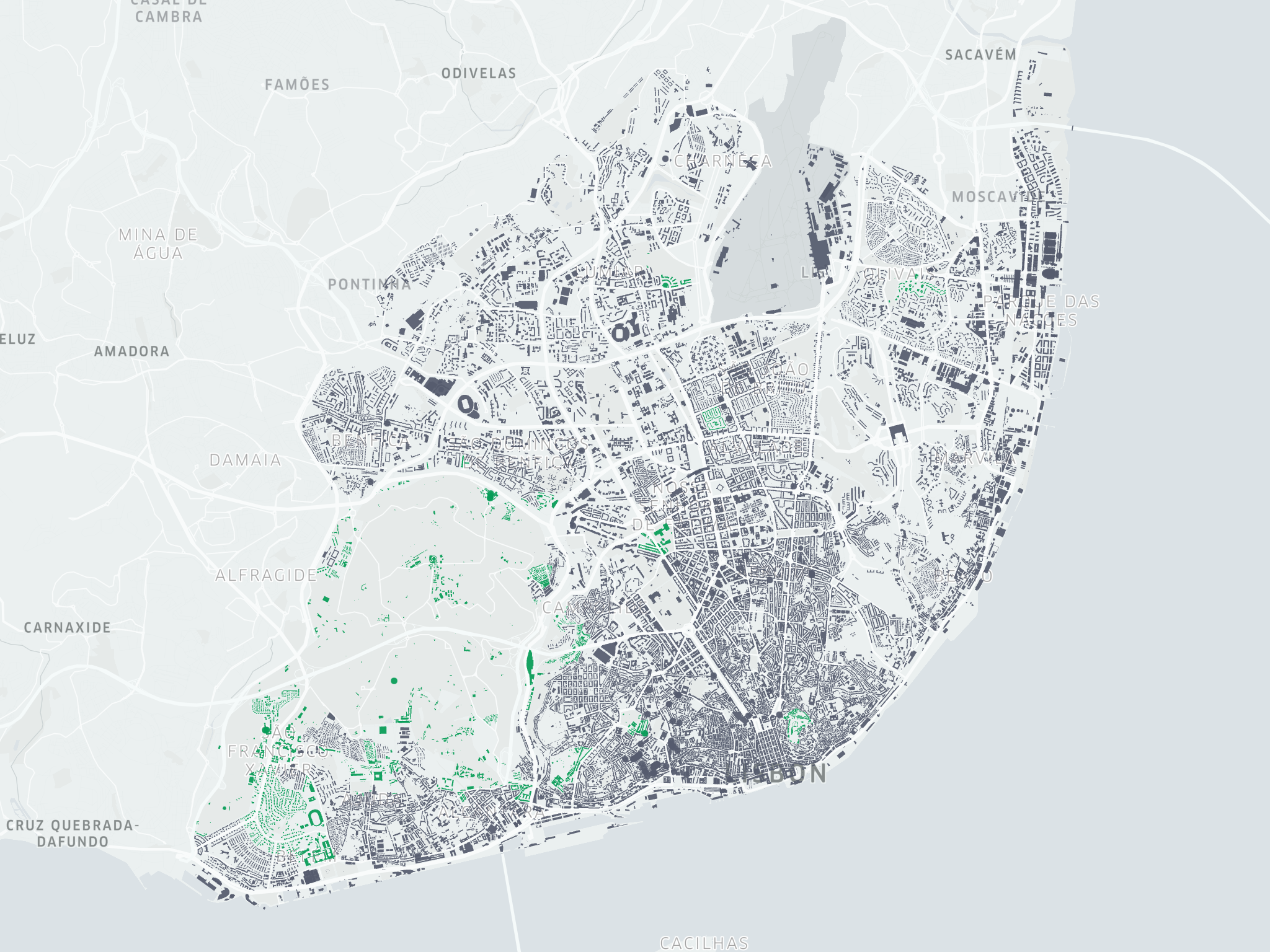

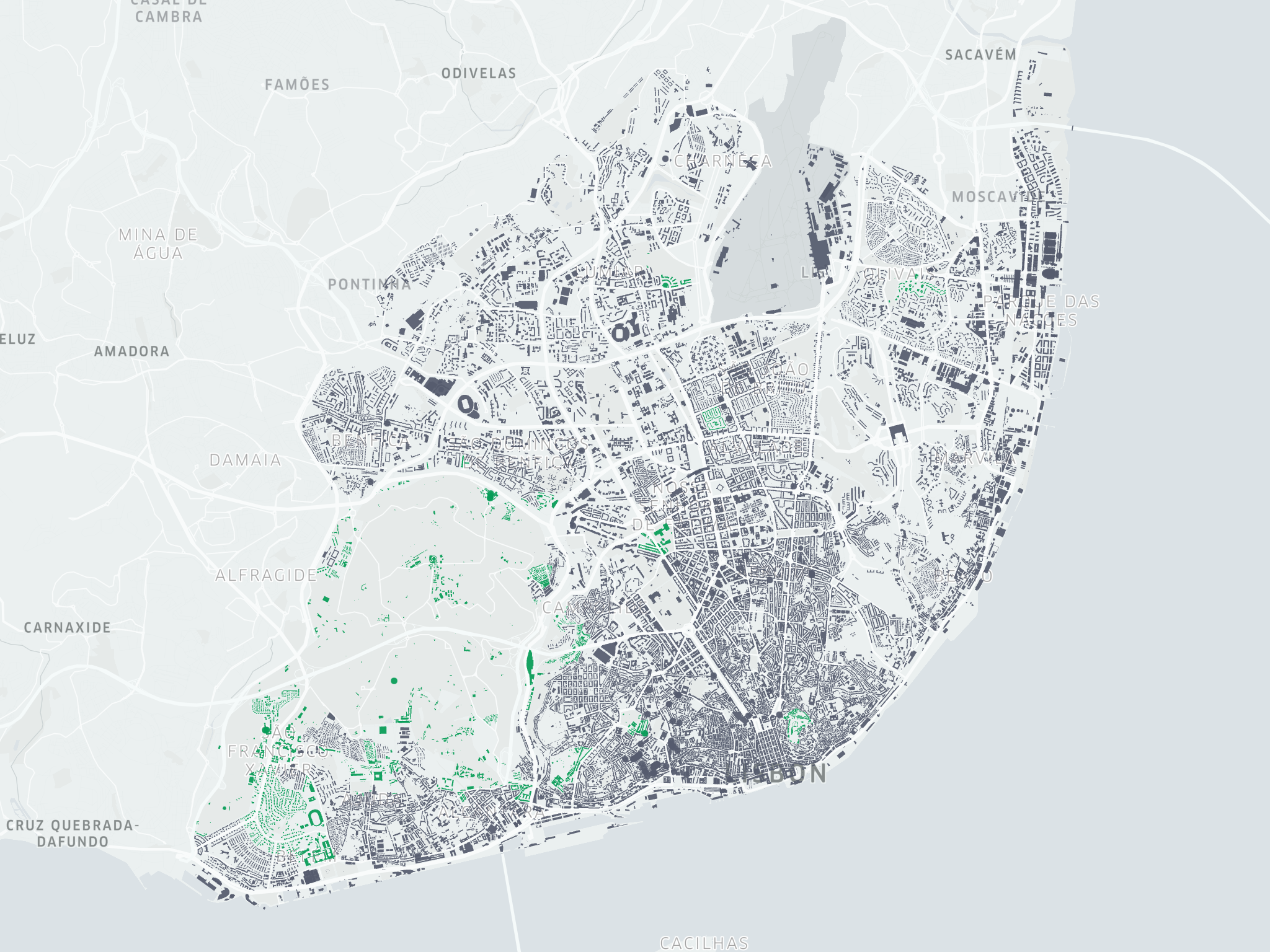

3 trees from the window

The presence of trees visible from our windows is beneficial for mental health and well-being.

It turns out that 44% of buildings in Lisbon comply with the three-tree rulein the north of the city and also in parishes such as Avenidas Novas and Parque das Nações. In the historic center, most do not meet this requirement. Trees, especially if their canopy is broad, can intercept and reflect up to 90% solar radiation, reducing people's excessive exposure to the sun. It also shades buildings, reducing the temperature of heat-radiating materials and the interior of homes.

Browse the map and find the place where you live (see the big picture):

30% green roof

Increasing tree cover to 30% in European cities could reduce deaths related to the urban heat island effect.

In this field, the ratio is quite different. The percentage of buildings in an area with 30% of green cover is only 7%. Through the analysis of 93 European citiesDuring the months of June to August, it was estimated that up to 39.5% of deaths attributable to high urban temperatures could be avoided by expanding tree cover to 30%. According to data from European Environment AgencyWhen we compare Lisbon with 37 other European capitals, we see that it is the 11th European capital with the lowest levels of green cover.

Browse the map and find the place where you live (see the big picture):

300 meters from a park/garden

A maximum distance of 300 meters to the nearest green space is recommended.

On this criterion, we can already see a very interesting scenario: 77% of buildings have at least 1 garden nearby. The World Health Organization recommends that the urban population should be no more than 300 meters from green spaces - and this reflects the importance of these facilities in promoting public health. Gardens, parks and squares are places for leisure and relaxation, for escaping the extreme heat, but they are also meeting places that foster local social relations between neighbors and create a sense of community and belonging. Ensuring equal access to these spaces is fundamental to creating healthy and sustainable urban environments.

Browse the map and find the place where you live (see the big picture):

Which buildings meet all the criteria?

According to our analysis, it is estimated that only just over 2% of all buildings (residential and non-residential) in Lisbon comply with the 3-30-300 rule.

The shortage is more pronounced when we overlay the heat island map. In the areas of the buildings that comply with the rule or the areas where Lisbon's large emblematic gardens are located, the heat island is practically non-existent. And we can also see that it's the lack of green cover that means many buildings don't comply with the rule. If we just used the rule of 3 trees and 300 meters of garden, the buildings that would be in compliance would be around 36%.

It is therefore necessary to think collectively about the necessary measures directed at these areas of the city to accelerate their occupation with green elements, in order to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change.

In a scientific article published in 2015 in the journal Urban Forestry & Urban Greening entitled Benefits and Costs of Street Trees in Lisbon, Portugal (Benefits and Costs of Trees on Lisbon's Streets) it is said that For every dollar invested in the management of a tree, residents receive 4.48 dollars in energy savings, air purification, increased housing value, reduced rainwater runoff and CO2. This meant that in 2011, when there were 41,247 trees on the streets of Lisbon and municipal maintenance costs were 1.8 million dollars, the return was 8.4 million that year.

In recent years, Lisbon has made some strides towards becoming a more environmentally friendly city, creating commitments to increase the number of green spaces and trees, albeit at a pace not suited to the current urgency. This achievement earned the city the award of European Green Capital in 2020, the first city in southern Europe to receive this distinction. In 2021, Lisbon City Council announced the creation of another 150 hectares of green areas by 2025 and an increase of 20,000 trees by 2030.

The rule and the heat island in BIP/ZIP

Given the lack of data on average salary/income by parish (or statistical section) from INE, we have resorted to a geographical language that is stigmatizing in itself, and which prevents us from investigating the territory in its multidimensionality - the BIP/ZIP, Lisbon's Neighborhoods and Priority Intervention Zones.

When we overlay compliance with the 3-30-300 rule with the BIP/ZIP limits in the areas most affected by the heat island, we see that the vast majority of buildings do not comply with the rule - as is the case in large areas of the historic center and its surroundings. There are a few exceptions in the Castelo de São Jorge area - mostly stores and services.

While we must pay attention to all the areas affected by heat islands, it is crucial to take care of the zones where socio-economic vulnerabilities accumulate. As a rule, these areas have less well-built homes, with lower levels of thermal comfort, smaller and more dilapidated.

The combination of intense heat, difficulties in air-conditioning housing and the scarcity of green areas in these places accentuates socio-economic disparities, perpetuating inequalities in relation to the rest of the population.

A public health and thermal comfort problem

According to the Lisbon 2030 Climate Action PlanThe air temperature in the Lisbon region has seen a general increase in both maximum and minimum temperatures, a scenario of continuous increase that is being maintained in the projections for the foreseeable future. As Jean-Francois Bastin shows in a 2019 articleIn 2050, Lisbon will be closer to the temperatures of Casablanca (Morocco) than the temperatures of Lisbon today. We need to prepare ourselves.

Extreme heat is starting to change our lives and, as a consequence, it's going to change the way we make cities. Currently, among the most substantial threats to cities are the impacts of climate change, which materialize, also because of urban morphology, in extreme temperatures - heat waves and the occurrence of urban heat island phenomena. (ICU).

Urban heat islands influence the well-being and health of people living in the city, but they don't affect everyone equally. The effects of climate change will always and invariably be more severe for the most vulnerable populations (e.g. the elderly) and those suffering the greatest financial hardship.

It is in this context that the collective need for making a city. Making a city is to politically dispute the direction we want for our city, to jointly build the distribution and composition of collective and private spaces, to demand and help develop the tools that allow us to democratically decide and intervene in the territory that belongs to all people.

Public Health

According to European Environment AgencySince 2000, much of Europe has suffered intense heat waves, with real impacts on our health and socio-economic system. Extreme heat is associated with increased mortality, hospital crowding and generally affects the sense of well-being and productivity of workers, learning and educational success.

The World Health Organization indicates a 50% increase in heat-related deaths by 2050. In Portugal, the deadly impact of heatwaves is already undeniable, as evidenced by a study in the scientific journal Nature Medicine that estimates more than 2200 heat-related deaths in Portugal during the summer of 2022.

This alarming (but correctable) scenario places Portugal among the 35 European countries analyzed as the country with the 4th highest number of deaths per million inhabitants, behind Italy, Greece and Spain.

In the same vein, the study "Urban heat: an increasing threat to global health" points out that UCIs have a direct or indirect impact on our health. Extreme heat has a direct effect on mortality and morbidity, and generally has more serious consequences for vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or people on low incomes who are often concentrated in urban areas where the heat island effect is higher.

To tackle this public health crisis, it is crucial that government action is combined with local political action and that heat is fully recognized as a real and imminent threat to people's lives.

According to the European Environment Agency, by 2040 the Lisbon metropolitan area will have a average of 15 tropical nights (nights with temperatures above 20 ºC) per year, with 88 nights expected by 2070. Cities such as Athens in Greece and Phoenix in the United States have already adopted a proactive approach to similar situations, with action plans developed from departments specifically created to study and mitigate the effects of heat.

Recognizing this need, the World Health Organization established the Chief Heat Officer" position with the aim of identifying and implementing solutions to mitigate heatwaves, recognizing the urgent need for measures to protect public health.

Thermal comfort

At National Long-Term Strategy to Combat Energy Poverty 2022-2050The socio-economic disparity becomes clear when we consider the asymmetrical distribution of the energy performance of homes. The inequalities emerge sharply when we analyze the increase in demand for energy consumption related to air conditioning systems and other cooling equipment.

Homes with low energy performance are associated with households with lower purchasing power, greater difficulty in remodeling or buying appliances with type A energy certificates.

Even when it comes to refurbishments with co-funding from the Environmental Fund, it is necessary for people to make the full investment and then wait for the state to reimburse them - time and resources that many Portuguese families don't have. As a direct result, many of these families don't have access to efficient air conditioning systems or, when they do, are faced with exorbitant electricity costs.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the consumption and demand for air conditioning to triple by 2050resulting in China's current total electricity consumption. As an example, London came dangerously close to experiencing a large-scale blackout in July this year, when demand for electricity peaked on exactly the hottest day on record in the UK. The tragedy was averted due to the intervention of the British electricity distribution company (ESO), which imported energy from Belgium at unprecedented prices (essentially to support lighting and air conditioning systems) in order to keep the capital running.

This scenario perpetuates a cycle of energy inequalityThis type of poverty, where those with fewer financial resources face greater challenges in their search for living conditions and health, thus contributing to deepening existing social and economic disparities. This type of social vulnerability associated with the difficulty of accessing facilities that provide protection against extreme temperatures, such as air conditioning systems, adequate ventilation or access to green spaces.

The scarcity of green areas not only intensifies exposure to high temperatures, but also limits the enjoyment of environments conducive to leisure, rest and socializing, typically disproportionately impacting the most socially vulnerable individuals and communities and the older population (65+ years of age).

It is in this population that we also find the clinical vulnerabilityThis refers to the susceptibility of individuals with certain health conditions to extreme weather events.

Extreme heat events also have an impact on the economic fabric and productivity or even on the way people relate to each other, sometimes leading to workers are forced to change their working hours, thus affecting their social routines. Even in situations where the heat doesn't affect professional performance, such as working in air-conditioned buildings, commuting to work can feel different. Workers who can afford to travel to work by car will certainly resort to air conditioning during hotter periods on their journeys - something that cannot always be guaranteed on public transport these days, where people are more crowded.

During periods of extreme heat, public transport systems have seen a drop in the number of passengersThis is because more people choose to stay at home or use their own cars, which ultimately contributes to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions. Active mobility options, such as walking and cycling, are also decreasing, especially if the paths are not shaded.

To tackle the difficulty of access to green spaces, shade and energy-efficient housing, it is crucial that government action is combined with local political action and that heat is fully recognized as a real and imminent threat to people's lives.

A proposal for recommendations and the role of local political action

The impact of the heat island effect is a reality today and will be a worse reality tomorrow, with social inequalities already being significantly anticipated, especially for the most vulnerable such as the elderly and the most marginalized communities.

According to one 2022 study by the Yale Program on Climate Change CommunicationAccording to the survey, 86% of the Portuguese population is alarmed (56%) or worried (29%) about the effects of climate change in Europe. We know that capitalism never solves the problems created by its crises, it displaces them geographically. Heat doesn't move, but people with more financial resources can, for example, choose to live in other geographiesYou can also improve the thermal comfort of your home or decide how to move around.

Our societies redistribute access to comfort and well-being unequally, either through permissiveness in the disproportionate accumulation of economic capital, or through a collective inability to apply urban policy measures to mitigate these effects.

We therefore need joint action between municipal institutions, collectives and citizens, we need local political action to unite with government action and fully recognize heat as a real and imminent threat to people's lives.

As inhabitants of Lisbon, these are some of the proposals we want to put forward for collective discussion. We don't accept them as finished, much less as prefabricated ideals for all areas of the city of Lisbon. To making a cityThe work must invariably be based on a discussion between government action and collective political action.

We propose the creation of Municipal Green Community Pact. We want to recover the principles of municipalism, with a strong focus on proximity, empathy and joint action. These principles will be the basis for creating contextualized solutions in a new, more horizontal and dialectical governance structure, combining platforms for participation, data analysis and active listening to people in order to prioritize actions. A common pact for a common problem.

- Opening of public infrastructures. The first of the measures we present for collective discussion is the opening up public infrastructure to people. We want to rethink the various types of use that a space can have depending on the time of year and time of day. Starting with schools, spaces that already have various facilities and are closed for a large part of the year, especially during the summer, the hottest time of year. Opening up these facilities to the public during vacations and weekends, making schools a crucial pillar in collective participation and one of the stages for citizens' assemblies to debate and create local proposals for the promotion and implementation of the Municipal Green Community Pact.

- Down with the sun, the shadow belongs to everyone. The aim of this measure is to have a rapid and surgical intervention program to install artificial shade using low-cost equipment. Any group of citizens can, by submitting a justified proposal, ask their parish council to install this equipment in the streets or parks/gardens of their neighborhood.

- Special Reconfiguration for Living and Experiencing Streets. In order for people to be able to use the urban space, which is for everyone's enjoyment, with shading, we propose activating the REVER. This measure allows people to come together collectively to open up their local streets to people at least two weekends a month for leisure and recreational activities.

- Green eyeshadow. Because many of the streets in downtown Lisbon require more complex interventions on the roads and sidewalks and the heat island effect is more severe, we propose this idea, which envisages the creation of suspended artificial shade with a green area for narrow streets in Lisbon's historic center. This infrastructure consists of triangular awnings from one end of a building to the otherThey reduce the temperature both around and under the awning. Thanks to the evapotranspiration produced by the vegetative system, the awnings act as particle mitigators, absorbing CO2 and helping to improve the city's air quality.

- 30 Verde neighborhood. It consists of creating tools that allow people or groups to identify places in their neighborhood to plant trees, through a locally-based program with the aim of the neighborhood reaching 30% of green coverage. An order is issued to the Town Hall and Parish Council to check on implementation and start the planting process with the population. This activity makes it possible to identify and speed up the installation of the Municipal Network of Climate Refuges.

- Municipal Climate Refuge Network. They are characterized by being places sheltered from the sun for meeting and socializing. These spaces can have a number of features that make them more pleasant, providing interactions between people, such as benches, spaces to carry out outdoor activities, games, shaded areas and other facilities that make the place a good place to spend time. In addition, climate refuges can also have leisure and entertainment elements, such as toys for children.

This work is licensed under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0This means that you can republish it in any medium or format, as long as it is unaltered and for non-commercial purposes.

Manuel Banza is passionate about Lisbon and his parish of Arroios. He has found in data analysis a way of communicating how mobility and urbanism can make cities more sustainable and humane. He writes about cities and how social ecology can help us build a healthy and inclusive future. She is a member of Rizoma Cooperativa Integral, a cooperative in Arroios that promotes the principles of direct democracy, proximity economy, network cooperation and decentralization.

Bernardo Fernandes is a sociologist dedicated to the study of issues surrounding territories. He has worked in the areas of youth, rurality, neighborhoods, public life and urbanism. He worked at Cooperativa RhizomeHe is also involved in the creation of the Integral Cooperatives Network - a forum for discussion and sharing of information, difficulties and successes; and in the creation of the Co-Habitar Network - a group of cooperatives and housing collectives. He is also involved in the creation of the Integral Cooperatives Network - a forum for discussion and sharing information, difficulties and successes; and in the creation of the Co-Habitar Network - a group of cooperatives and housing collectives in AML fighting for the right to cooperative housing in collective ownership.

This first Fazer Cidade article was written by just two people, but the aim is to change that from now on. If you like this work, are interested in topics related to the city and would like to suggest a topic and write about it with us, send your idea to disputar@fazercidade.pt. Fazer Cidade is a group of people who want to think collectively about the city of Lisbon through a partnership with local and community newspapers.

Analysis methodology

The following data sources were used:

- Lisbon Buildings (Open Street Map)

- Trees in Lisbon (Lisbon City Council)

- Lisbon's green spaces (Discord LPP)

- Tree Cover Density, 2018 (Copernicus)

- Street Tree Layer - STL, 2018 (Copernicus)

To process the data and calculate the rule, the following steps were taken:

- Buildings: First, we imported all the buildings in Lisbon using the Open Street Map. Then we created centroid (most central point of the building) for each polygon representing each building. This point will be the basis for calculating the three rules (3, 30, 300);

- Rule 3: used the dataset Trees in Lisbon. Lisbon City Council is responsible for updating the data, so if you find any inconsistencies in the data, you can help the municipality and the city to have a better understanding of it. dataset as soon as possible by sending an e-mail to geodados@cm-lisboa.pt. With this datasetA radius of 50 meters was calculated from each centroid (the central point of the building) and the number of trees within that radius;

- Rule 30: First, the data was imported from Copernicus satellite images. Tree Cover Density 2018 e Street Tree Layer. Next, the data mentioned above was cross-referenced with the Lisbon tree points used for rule 3, in order to check if there were any trees that were not accounted for in the satellite images. Where this was the case, it was decided to assign a radius of 1.5 meters to each tree, in order to simulate a tree canopy. The value of 1.5 meters is quite conservative, but was chosen because it is quite difficult to predict according to various studies consulted. The average value for the most recent trees was used, not least because these are the trees implemented after 2018 that are not shown in the satellite images. Finally, the area of green cover was calculated for each statistical section provided by INE, using the data from the points above;

- Rule 300: the dataset Lisbon's Green Spaces. They are updated by the Lisboa Para Pessoas Discord community, and it was found that there were more recent parks that were not included in the CML data. The layers that fall under gardens and parks only were used. Next, a radius of 300 meters was calculated from each centroid (the most central point of the building) and identified whether this radius intersected any of the gardens or parks.