History Labs can help develop a collective agreement on highly controversial issues, through the past and joint work between historians, citizens and technicians. Colin Divall has dedicated part of his life not only to creating History Labs, but also to thinking about the present and imagining the future from the narratives and constructions of the past. In this interview, he shares some of that knowledge with us.

Whether we realize it or not, the future of urban mobility is shaped by its past. And looking to the past can help us realize that there are no inevitabilities in today's patterns of urban mobility - because they result from choices made historically between different and competing visions of what a city should be - and learn about a reservoir of alternative visions. Colin Divall discusses these ideas about the "usable past".

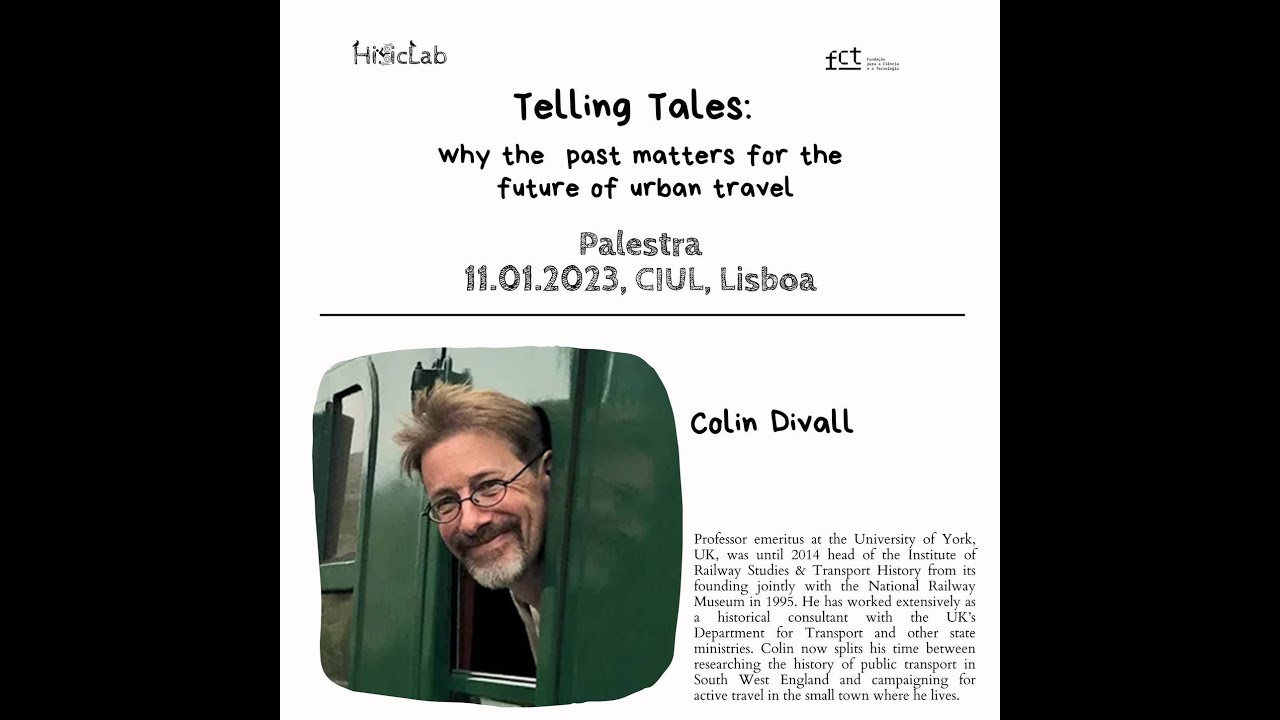

Colin Divall is a historian. He was Professor of Railway Studies at the University of York in the UK, and has studied how, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, certain narratives influenced the development of the British railroad in relation to the road. More broadly, he has tried (and continues to try) to understand how our past attitudes towards mobility can shape the contemporary development of greener and more socially sustainable transport policies.

Now retired from his university, Colin is working as a consultant on a research project in Lisbon, the Hi-BicLabHe is trying to understand what the city's past can say about the present, not in relation to the railroad, but to the bicycle. "For many years now I have a strong interest in trying to understand how history can be applied to current civic issues, especially with regard to mobility. Both during the period when I was working full-time and since retirement I have been involved in various projects that have sought to relate history to various transport policy issues."he told LPP in an interview. "And although my work as a professional historian is mainly related to railways, I've been cycling for a long time, since I was a child. I've always had a very, very strong interest as a citizen in what we now call active mobility."

In the context of Hi-BicLab, Diego Cavalcantihistorian and researcher in the aforementioned research project, and M. Luísa Sousa, also a historian and the researcher in charge of the project, we conducted the interview with Colin Divall for LPP, which is now published here.

What is the role of history in addressing contemporary issues and how can it contribute to changes in current topics such as climate change and sustainable mobility?

First of all, we have to be very clear about what the story can't do. Understanding the past - however well we understand it - does not produce a recipe book, a set of instructions that we can take from the past and apply to the present. Historians far more eminent than myself have often said that history not repeats itself. Once we understand that, we realize that there's no point in hoping that we can go back and understand, for example, why freeways were built in a particular city and what kind of opposition there was, and take from that a set of instructions on how to oppose plans in the present; or even how to successfully campaign for new cycle lanes, or any other issue: the circumstances are always different. On a more positive note, from my perspective, I believe that the most powerful way for history to contribute to current political discourse and campaigning around active mobility, or any other topic, is to think of it as a way of opening up or freeing our imagination to the possibilities of the future. I think this is a fairly simple idea, but one that needs to be explained in detail.

"If we want to make a radical change, if we want to transform a city like Lisbon from being dominated by cars to a much stronger role for active transportation, such as cycling and walking (which is a big change), then we have to take the citizens with us. We have to take citizens with us, as well as elected representatives and the institutions in which policies are formulated, among others. One key to doing this is to develop stories and narratives that trigger people's imagination for this very different future."

I think we need to get a sense of how radical political change can happen, or become possible in the present, early 21st century. I've been very inspired by a number of political activists, most notably the British activist and environmental writer George Monbiot, who argues that radical political and social change is driven as much by emotions and passions as by rational arguments. This not is a reason to abandon evidence-based arguments, but to recognize that in order to effect political change, especially in democracies, it is necessary to win the support of citizens. Citizens tend to get involved in political campaigns as much through emotion and passion as through rational arguments.

So, if we accept this, the consequence is that if we want to make a radical change, if we want to transform a city like Lisbon from being dominated by cars to a much stronger role for active transportation, such as cycling and walking (which is a big change), then we have to take the citizens with us. We have to take citizens with us, as well as elected representatives and the institutions in which policies are formulated, among others. One key to doing this is to develop stories and narratives that trigger people's imagination for this very different future.

How can we tell these stories?

Storytelling is something we do in the present to stretch people's imaginations about future possibilities. But this form of storytelling in the present needs to refer back to the past, or should refer back to the past, to produce a convincing narrative that demonstrates why we are in the current circumstances, why we live in a city like Lisbon, London or any other city, which is so dominated by the car, to demonstrate that there were other possibilities in the past and that that past could have been different. And to help people understand that things could have been different in the past and therefore, I would say, could be different in the future.

"I don't think it's necessary to convince everyone with your narrative. There are turning points when you convince a significant minority of citizens, perhaps around 20 to 25%, that the future you are envisioning is possible. But it's important to develop powerful and convincing stories.“

I don't think it's necessary to convince everyone with your narrative. You don't need to involve 100% of citizens. Current work on political change suggests that there are tipping points when you convince a significant minority of citizens, perhaps around 20 to 25%, that the future you are envisioning is possible. This can create a tipping point where the campaign really starts to gain momentum and you can start to get the support of politicians and policy-makers, among others.

But it is important to develop powerful and compelling stories; this is central to how I understand how history, how our understanding of the past, can free our imagination for a much more radical future. So, by looking to the past, I'm suggesting that we can begin to free ourselves, to free our imaginations from the kind of dominant, incompletely remembered assumptions and narratives that do so much to maintain our current ways of getting around cities and that restrict our imaginations, limiting them about different and more radical forms of mobility in the future.

Is it through stories that we can counter the idea that car mobility has always been inevitable?

What I'm advocating is a kind of history that develops narratives that, in turn, liberate people from a mentality locked in the present, a mentality that makes people literally can't conceive of more sustainable ways of getting around the city. So what I'm really calling for, what we're trying to develop, is a way of understanding the past, a way of telling stories about the past, which feeds into what I'm going to call a cultural policy of sustainable urban mobility in the present.

So these are stories that will engage, convince and inspire enough people, perhaps this proportion of 20%, 25% or whatever, as citizens, academics, policy analysts and decision-makers to actually dream. Dreaming and working towards a future that otherwise seems impossible. So it's a form of storytelling that looks to the past and informs us about how we got to where we are in the present. In doing so, it frees our imagination for the future.

"The past has been the subject of disputes. It was a contested process. There were different opinions - different people had different ideas about how the city should evolve, and the mobility pattern we find today was not inevitable. There were options in the past, and choices were made at a certain level that took us down one path and not another."

How do we actually do that? What does this kind of history entail? Well, I and other people call it the "usable past". "Usable" in the sense that it's a way of understanding the past, a way of understanding history that is driven by this imperative to tell stories that free our imagination for the future. I think there are three elements to this that I believe - actually, I don't believe, I know - have already been incorporated into your History Lab project.

I think we need to make it very clear to ourselves and to the public that the past was the subject of disputes. It was a contested process. There were different opinions - different people had different ideas about how the city should evolve, how we should move around the city, and the pattern of mobility we find today not it was inevitable. There was options in the past, and were we made choices at a certain level that led us down one path and not another.

But aren't we, in a way, stuck in the past?

I think that going back to the past also allows us to understand the other side of this perception that there were alternatives. And this other side is that the choices were or power struggles have been resolved in one way rather than another, and we tend to get stuck in path dependencies. In other words, once you've made that decision, once you've decided to build that urban highway or that main road, instead of building cycle paths, it becomes, in a way, almost inevitable that people will start buying cars, motorcycles or whatever and follow the path of automobile mobility.

It becomes much more likely that people will stop using their bikes or walking, especially as other elements of the city, such as where factories have been built, where workplaces have been built and where leisure facilities have been built, start to develop around the emerging system of automobile mobility. So we are trapped in this dependency. There are physical dependencies that are reflected in the physical infrastructure that is being built. This makes it difficult, but not impossible, to change the way we move around in the future.

But, returning to a point I mentioned earlier, I think we also acquire path dependencies in our ways of thinking, forgetting that there were alternatives, forgetting that there were other views on urban mobility. Today, we find ourselves being literally unable to think of alternatives, partly because we forget that there were alternatives in the past that were well-founded and passionately defended, and that could have come to fruition.

So, once again, I'm repeating what I said a few minutes ago. The past, this usable past is, at least in part, a reservoir or depository of lost visions, of lost or only vaguely remembered ways of imagining urban mobility. We can dig into it, we can go back and retrieve it and, while acknowledging what I said in my opening remarks - that the present and the future never exactly repeat what happened in the past - I think that these echoes of the past, these alternative visions, can be used to inspire us and to re-imagine these lost visions in the context of the present, to imagine, and even adopt, a very, very different way of moving within cities.

"In the present, we find ourselves literally incapable of thinking of alternatives, partly because we have forgotten that there were alternatives in the past that were well-founded and passionately defended, that could have been realized."

So my usable past is a kind of cultural history. It's a form of storytelling that seeks to go back into the past to excavate these lost visions that ignite our imagination for the future. To give us hope: it's about giving us hope that things can be different. It's very difficult to have hope most of the time, but for me, history is a source of encouragement - it gives us hope that, in the long run, things can change and they can change for the better.

In your research, in addition to official documents such as the Buchanan Report (1963) and the Beeching Report (1963), you also worked with newspapers, editorials and letters to the editors. How did this use of different sources allow you to build a more detailed understanding of the narrative disputes surrounding urban mobility in the 20th century?

The question contains the answer, in fact. That's exactly why I'm looking at sources outside the official narrative. Obviously, official documents are very important. Perhaps we should mention that the case study I've worked on most deeply is about the development of urban and suburban mobility in what is now, at the beginning of the 21st century, an urban region on the south coast of Dorset, the county where I live - the conurbation of Poole, Bournemouth and Christchurch.

I'm analyzing the history of this region from around 60 years ago (which happens to be the period when I grew up in this area) and trying to understand how a railway system that served this area quite comprehensively, when it was much less developed than it is now, essentially rural railroads, ended up being abandoned and how the emerging urban region became heavily dominated by cars, by automobile mobility.

Understanding the official documentation is really important, not only to understand the elaboration of different arguments within the state, at the national level, in the then Ministry of Transport, but also at the level of what we now probably call regional government. It is necessary to understand how different arguments were presented, often in those days confidentially. The public, the citizens not were involved in these kinds of discussions. If we don't understand that, we won't understand why the policies were enacted the way they were, why the decisions were made the way they were.

"It's necessary to understand how different arguments were presented, often in those days confidentially. The public, the citizens, were not involved in these kinds of discussions. If we don't understand that, we won't understand why policies were enacted the way they were, why decisions were made the way they were."

On the other hand, we are lucky enough to live in democracies, albeit imperfect, liberal democracies. And in these types of systems, even civil servants, even elected governments, have to pay close attention to what citizens are thinking. It's not impossible, of course, for governments to enact unpopular measures, but it's much easier if the government is going with the flow. So what I've been trying to do, especially by looking at newspapers, editorials, letters to the editors, opinion pieces, as we now call them, is to understand, albeit imperfectly, these broader currents of thought within the general population.

And in doing so, I discovered many alternative visions, different ways of thinking: people, citizens and some organized groups who had very good arguments about, for example, why this loss-making rail system should not be shut down. These citizens, these advocacy groups, had a very clear idea - or perhaps common sense - looking at what had been happening in the United States over the previous decades, that automobile mobility, or an almost total dependence on automobile mobility, had many drawbacks. And they argued that the local rail system, although at the time, in the early 1960s, it was losing a lot of money, had enormous potential to be the backbone of a different way of moving around in this emerging urban region.

So I think this particular case study is a good example of how we can go back in time and find alternative visions. I also made use of oral history for the same purpose, because this is still within people's living memory. But those of us who are professional historians know that there are various challenges when using oral history accounts. On the other hand, there are also advantages, and the advantage is that you can learn something that, for one reason or another, has never appeared in the written record, or at least not in what we might call the public written record, such as newspapers and so on.

So I think, if we have the time and the resources, we can analyze all kinds of sources - like private letters and diaries, and so on - and continue this process to get an even more nuanced understanding of the ways in which different groups of citizens were thinking about future mobility. But none of us has unlimited time and resources.

How important is it to contextualize key words like "modernization" and "sustainability", given that they can have different meanings? As historians, how can we do this?

I think there are two main reasons why it is necessary to contextualize these concepts historically. First, we must remember that we are talking here about history as a usable past, about going back to the past to develop stories about the past that inspire us for the present and the future. This means that if there are words that are being used today - and the concept of "sustainability" is certainly one of those in use today, and, I believe, so is "modernization" - if we go back in time and find these words being used in the past (which isn't very likely with the term "sustainability", but is certainly the case with the term "modernization"), we'll be able to use them in the future.

In my case study, the urban region of south-east Dorset, much of my analysis seeks to understand the way in which the term "modernity", or "modernization", was being used), so first of all we have to be very clear about how this word was used in the past, to make sure that we don't we assume that the way we understand this word today is the same way it was used in the past. So this is a simple rule of historical research: you have to be careful not to use a word anachronistically. Just because the word is the same, the meaning may be different.

"For example, when politicians began in the 1960s to associate the description of 'modernization' or 'modernity' with practically every urban mobility or urban transport policy they proposed at the time, for me as a historian, that was a warning sign."

So the first reason is that we need to check whether the word "modernization" was being used in a similar way in 1963 or whenever. More interestingly, when we look at the past, we need to understand the variety of ways in which a term like "modernization" was being used. Because, for example, when politicians started in the 1960s to associate the description of "modernization" or "modernity" with practically every urban mobility, or urban transport, policy they proposed at that time, for me as a historian, that's a warning sign. It's a warning that this word is being used because politicians believed it had a certain appeal to the public, or to certain key elements of the public, to citizens. And it's being used to generate support and enthusiasm for a specific set of policies.

This means that, as a historian, I want to understand the way politicians are using this word to gain popular support. Now, we've already talked about the different visions of urban mobility in the past in the area I was looking at, and I also find that these alternative visions, these citizens, these advocacy groups, who have proposed different ways of understanding urban mobility, also understandably like to use the term "modernization"; but the point is that their understanding of the term "modernization" involved a different vision, a different set of ideas about how to move around the city.

In simple terms, the dominant political discourse, both at national and regional level, saw "modernization" in the direction of an urban region based on automobility, with restrictions on public transport to relieve pressure on the city center; while alternative visions, those who wanted to see the railroad system maintained, also talked about "modernization", but for them "modernization" meant building a new type of railroad. Sometimes quite incrementally, such as introducing new forms of traction, changing timetables, and so on; sometimes more radically, with proposals to open new lines or develop new forms of technology.

"The same word is being used in subtly different ways by different groups, and an essential part is recovering these different meanings so that, at the beginning of the 21st century, we can develop our stories that will allow us to think in different ways."

But the key point here is that the same word is being used in subtly different ways by different groups, and an essential part of this is recovering these different meanings in order, at the beginning of the 21st century, to develop our stories that will allow us to think in different ways. And one of the things I did in my case study was to draw a parallel between the way the term "modernization" was used in the early 1960s in many different ways, with the way the term "sustainability" came to be used in the early 21st century in different ways too.

Everyone is in favor of "sustainability". The problem arises when you dig deeper: you realize that different groups have different understandings of what the term "sustainability" means. So, in this specific case, understanding the diversity of the use of the term "modernity" or "modernization" in the past alerted me to the very different ways in which the term "sustainability" came to be used at the beginning of the 21st century by politicians and other people involved in urban mobility, but also more generally. And so I've come to describe these terms, such as "modernization" and "sustainability", as agglutinating terms in the sense that they are words that, as it were, work like big bags.

Any meaning can be thrown into them to serve a certain purpose, with the consequence that, in a way, the words end up becoming almost insignificant. But that's in a dangerous way, because it's possible for people to think "oh, this is a good policy because it's about sustainability", without really understanding that the word is being used in one sense and not another.

If you always define what you mean by "sustainability", it's fine to use that term. But of course that's not what happens in political discourse, especially when politicians are trying to sell an idea. So history acts as a warning here. But once again, at the beginning of the 21st century, I return to this idea: what interests us here is the present and the future. We have to analyze these agglutinating terms in the context of the politics of the early 21st century.

What about the use of these terms by experts and their presence in the experts' discourse?

Well, I'd like to think that experts will be more careful when using terms like "sustainability" or "modernization". But I think that if I can describe myself as an expert, at least when it comes to understanding the history of certain types of urban mobility, I sometimes catch myself thinking "what do I mean by this term?" It can be slippery, it can be very slippery.

"I think when we're trying to engage the general population, we have to be very careful to make it clear which use or which sense of the word 'sustainability' we're using, in a specific context."

Most of us who have been interested in urban mobility for some time are well accustomed to the idea that the term "sustainability" has at least three dimensions: economic, financial "sustainability"; social "sustainability" (which I think generally refers to the sense that any change should be equitable, should not favor one part of society over another; or else it should favor, should discriminate in favor of, the less advantaged); and, finally, environmental or ecological "sustainability", which is about how mobility fits into the wider ecosystem.

I think that when we are trying to involve the general population, we have to be very careful to make it clear which use or which sense of the word "sustainability" we are using, in a specific context.

I'd like you to explain what a History Lab is and what your expectations are when implementing this approach, for example, if you're doing as you are with Hi-BicLab?

I'm very interested in what you [Hi-BicLab] are doing, because I believe that what you're doing is really much more radical compared to everything that my colleagues and I have achieved so far in the UK; but maybe we can address that later.

The term "history lab" is not my invention. I believe I picked it up in the Netherlands. I'm pretty sure that's where the term first appeared, and I understand that the Dutch conceive of it as a way of involving individuals and groups in society in order to collectively learn from the past, with the aim of developing stories that help us situate ourselves in the present and inspire our thinking about the future. I believe that this kind of collective effort perhaps has parallels with the idea of citizens' assemblies, with which you are probably familiar.

Are you talking about Bert Toussaint's work at the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure? And T2M [International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic and Mobility], which also tried to promote a debate on history and public policy a few years ago?

Yes, I believe that, like many things, it was a two-way, or multi-way, process. I think Bert Toussaint's work at the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure was especially inspiring because he and his colleagues really put a History Lab into practice. They managed to get significant institutional support, which ultimately translated into funding! Bert was hired by the ministry to develop various ways of learning from the past, the History Lab being just one part of this.

And yes, you're right, T2M also followed this idea. I was having discussions with other colleagues in the UK who at that time weren't particularly involved with T2M, but were involved in, for example, academic departments in the field of transport studies, or transport policy, and some of these individuals were actively involved in campaigning on mobility-related issues - not necessarily cycling-related, but I think we all shared an interest in that. A lot of different threads were interwoven.

So working in the UK is by no means unique. I have to say that I'm slightly I'm disappointed that the idea of the History Lab hasn't taken firm root in the UK. It may well be that I'm simply unaware of some initiatives because I'm not as involved in professional networks as I used to be. It's true that I still work with the UK Department for Transport, and I suppose this particular version of the History Lab is probably quite close to the kind of work Bert was doing at the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure a few years ago.

"It would be useful to know if, in the 1950s or 1960s, or at any time, there were people in Lisbon who argued strongly that the bicycle should continue to be a fundamental part of mobility in the city? Or was it something that wasn't even discussed? It could be something as basic as that."

In general terms, I believe that a History Lab has the potential to do several things. Again, I come back to the fundamental point that we are trying to develop a set of stories about the past that can inspire us about the future. This is the main goal; but I think there are several steps in this process that a History Lab can contribute to, not all of which are achieved by the kind of work I do with the Department for Transport. That's why I believe that, in the first place, a History Lab can help establish, through conversations between experts, citizens, legislators, politicians, in short, as many groups as possible are involved, what can be useful to understand about the past in the present. This could be something as basic as: would it be useful to know whether, in the 1950s or 1960s, or at any time, there were people in Lisbon who argued strongly that the bicycle should continue to be a fundamental part of mobility in the city? Or was it something that wasn't even discussed? It could be something as basic as this.

So it's a conversation, a debate that helps people understand what might be useful to know about the past in order to inspire us for the future. A History Lab can be a way for this conversation to develop so that we can actually do an analysis. We can ask ourselves, as historians, as experts, what we already know about the kinds of things that this conversation has suggested might be useful to know.

And if we can broaden the scope of the History Lab to include citizens and advocacy groups, we can also see if these so-called "non experts", citizen historians or laypeople, or whatever they call themselves, can know things about the past that we experts have missed, because we may be experts, but we don't have a monopoly on understanding the past.

"Citizen historians can know things about the past that we experts have missed. We may be experts, but we don't have a monopoly on understanding the past."

What is the importance of bringing various non-historian audiences into contact with historical sources?

In my opinion, listening to other groups, promoter groups, citizens, whoever, is a really important part of a more complete History Lab, in order to understand what people know that we, as experts, don't know. I think this dialogue needs to go even further, and ask if there are other aspects about the past that we know but don't see as potentially relevant to our current political circumstances.

These conversations can bring up strange and wonderful ideas, some of which prove to be relevant. That's why workshops are such a fruitful way of working, because unexpected stories can emerge, and we only realize their importance by having this kind of conversation. But after all that, after we've gathered our collective knowledge and decided that it would be useful to know about X, Y and Z, but that in fact we've already we know about XY and Z, we also realize that there are gaps in our knowledge. There are things we'd like to know, but between us we still don't - what politicians in Lisbon were saying about urban mobility in the early 1960s or early 1970s. Maybe you know the answer, I don't. But if you don't, then you are starting to develop a research agenda, which can then guide historical research by experts, by citizen historians, to help build these inspiring stories about the past.

And finally, I believe that a fully-developed Story Lab can help identify what I call "product champions" - the individuals working within specific organizations or specific groups, who the workshop helped identify as potential key players in any future development of mobility policy in Lisbon, or wherever.

These "product champions" are the individuals, or small groups of individuals, who would commit to working within these key organizations to try to incorporate this historic approach to thinking about future policy into these organizations.

"Corporate memory is really very short, and I've experienced that within the [UK] Department for Transport."

So there is life beyond the History Lab, which in itself is not a one-off event - it's an evolving process - but there is life beyond the History Lab for this historical understanding of politics. Because otherwise there's a real danger, and unfortunately I think this is what's happened in the UK, that you can have one, or two, or three, or four, half a dozen, whatever, very successful history labs, where you have these really inspiring conversations, you can even do a lot of historical research that's really interesting in its own right, but also has relevance to actual policymaking - and then nothing happens, because you've done publications, blogs, newspaper articles; but then the people in the key organizations who can actually lead to some change just forget about it. They say: "ah, that was interesting".

But the reality is that corporate memory is really very short, and I've experienced that within the [UK] Department for Transport. I've been doing these History Labs with Charles Loft for... I don't know, I've lost count now, eight years, something like that, maybe more, and for obvious reasons, we haven't done one in the last two years, and so I thought maybe it was time we did another one. I sent an email to the Department for Transport. They said, "ah, that sounds like a really interesting idea, but we don't have any knowledge of it. Are you saying you've done this before?" I said, well, "yes, at least five times"; there's been a change in personnel, the records may be there, but you don't know that the records are there. I'm not saying I had to reinvent the idea, but I certainly had to sell it again.

How can we deal with this short memory?

In a sense, this is trivial, but for me it was a real wake-up call that corporate memory is really, really short. So now you can understand why I'm so interested in the idea of the "product champion" existing. A product champion is an individual who can leave the place they're in and so you still have the same problem; but maybe someone is working within the organization - like Bert Toussaint in the Netherlands, who I think you could argue is the kind of product champion I'm advocating -; someone who can create a strong enough corporate memory that it becomes second nature for organizations to think about policymaking with history as part of the equation. I'm not suggesting that history becomes crucial in all cases: but that within the organization systematic consideration is given to how historical understanding can contribute to better policymaking.

"I'm not suggesting that history becomes crucial in all cases: but that within the organization systematic consideration is given to how historical understanding can contribute to better policy formulation."

So I think this is the ideal, but it's extremely challenging. Extremely challenging. And the workshops that I conducted at the Department of Transport with Chas [Loft], as I said earlier, I believe are roughly equivalent to what Bert Toussaint did within the Ministry [of Infrastructure, Netherlands]. That's less challenging, much less challenging than what I understand you're trying to do, because within the Ministry, within the Department, we have a very defined group, or audience, that we're working with, and we know that we're dealing with mid-level and senior civil servants, who formulate policy - whatever you want to call them, policy advisors - who have a basic understanding of the kinds of concepts that we're talking about.

By this I mean that they don't have a real understanding of the historical case studies we're going to use, but they're ready to deal with it. They like to have a three-hour "break", in inverted commas, where they can participate and work a bit on history. They really get involved. We speak more or less the same language; although Charles and I have to remind them that historical terms in the 1960s weren't necessarily in use, or that those words weren't being used in the same way as they might be used today.

But all in all, I think we've succeeded in getting policy advisors to put themselves in the context of 60 years ago and try to understand the kinds of challenges that their predecessors faced half a century ago, or more, and then use these insights that they've developed over a few hours examining original documents and so on, to reflect, to turn around 360 degrees, well, 180 degrees, and reflect on the way they're proposing policies today.

This is the key point of the historical approach we are working with. We're saying to them: "look, we're not asking you to understand every subtlety of the rail, road and urban mobility policy of the early 1960s. We're asking you to go back in time to recognize that, in some ways, things were done differently back then and ask yourselves whether now, at the beginning of the 21st century, the way you're developing policies is appropriate to the needs, considering the advantages and disadvantages you now understand about the way of doing things in the past."

"We've managed to get policy advisors to put themselves in the context of 60 years ago and try to understand the kinds of challenges that their predecessors faced half a century ago, or more, and then use these perspectives that they've developed over a few hours examining original documents and so on, to reflect, to turn around 360 degrees, well, 180 degrees, and reflect on the way they're proposing policies today."

So one specific question we challenge them to think about is whether mobility or transport policy in the 21st century within the Department is being conceived in terms of decade time scales which, we now know from our understanding of what happened in the 1960s, are appropriate for this kind of policy area.

And that sometimes leaves them thinking. Sometimes they say "yes", and sometimes they think "yes, maybe we should think a bit more long-term than we do now". But I think that's challenging enough, even though it's much easier than what they're doing in Lisbon. Because my understanding is that, in Lisbon, they are trying to involve, or develop, a much more comprehensive way of doing history, developing a usable past, which involves groups outside the political elite, outside the local politicians.

They're trying to interact with citizens and promoter groups in a way that we certainly haven't tried to do at the Department for Transport; what we haven't managed to do, I don't believe we've managed to do systematically anywhere else in the UK - but I could be wrong on this point.

What are the advantages of involving non-historian audiences? And here we are talking about various audiences, not just the political elites, as you mentioned. And what are the pitfalls?

The huge advantage of involving a variety of citizens, as widely as possible, in Lisbon or wherever, is that we all have a sense of our collective past. Everyone who takes part in a History Lab will have some idea of stories, or how things developed in the past, related to urban mobility.

Even if it's just a repetition of the dominant narrative that it was inevitable that automobility would dominate Lisbon, or any other city. But the fundamental point is that we all have a sense of the past, and that's an advantage because, as I said before, those of us who consider ourselves experts on this topic don't know everything, and it's entirely possible for so-called non-experts, citizens, to bring fresh ways of thinking about the past into the conversation, the debate, the discussion.

"The huge advantage of involving a variety of citizens, as widely as possible, in Lisbon or wherever, is that we all have a sense of our collective past. Everyone who takes part in a History Lab will have some idea of stories, or how things developed in the past, related to urban mobility."

So I think this is the positive side. Not only telling specific stories about the past, but also bringing to the debate different perspectives on what is important in the present. It's important to remember that these history labs aren't just about understanding the past for its own sake - as important as that is for us historians - they're about understanding the past in order to influence the present and the future. So what matters in the present and what might be relevant for the future, for these different groups, can have a strong influence on the kind of stories we want to look for, the kind of things we want to understand about the past.

Now, how important is it for specific groups in Lisbon to improve the conditions for cycling, for example? I'm sure you're reaching some citizens, some groups, for whom it's not a priority. But even if it's not a priority, I think these groups should be included in the conversation, precisely because they have a different vision. They can question, they can enhance your thinking about why cycling and other forms of active mobility can be so important. They can also help you understand how a compromise could be reached between these points of view, which, at first glance, may seem completely opposed to each other.

"I'm sure you're reaching some citizens, some groups, for whom this [improving conditions for cycling] is not a priority. But even if it's not a priority, I think these groups should be included in the conversation, precisely because they have a different vision."

So I think there are several reasons why it's really important to reach out to different groups in a History Lab. The downside is that some narratives of the past actually amount to little more than a myth. They are misunderstandings or misreadings of the past. It's important to recognize that citizens have these views, but I think it's also crucial that, in a History Lab, we introduce the idea and make it clear that academic knowledge, or rigorous research techniques are really important, because they allow us to arrive - and I'm going to put this term in big quotation marks - at the "truth". (We could have another discussion about what we mean by "truth" in the historical context - but let's stop there!)

And what role does the academic method play in arriving at the "truth"?

The kind of techniques we develop as academic historians are also used by other people who are not academic historians, who are lay historians. The techniques of academic knowledge, in a way, allow us to understand the past more precisely - can I put it like that? - to get closer to the truth about what happened. And I think this is a key element of the History Lab, trying to develop a shared collective understanding - which, however, can still allow for a range of viewpoints. And the way we do that is by introducing the idea of rigorous research, or academic knowledge. But that can be really difficult.

"Some narratives of the past really amount to little more than a myth. They are misunderstandings or misreadings of the past."

Going back to the idea that politics is as much about emotion and passion as it is about rational arguments: people can be very attached to certain incompletely formulated understandings of the past, which I would argue are myths, such as: "yes, we know that the reason the car is so dominant is because there was no alternative. It was completely irrational to suggest that there could be other ways of developing means of transportation within the city, blah blah blah." It's difficult. It can be really difficult - to put it simplistically, or arguably oversimplified - to move from myth to a shared collective understanding of the past that we could describe as a usable past.

But I still think it's worth the effort, even though it's a challenge; as I mentioned earlier, I think the History Lab should perhaps be considered as a kind of Citizens' Assembly that looks back on the past.

"I think the History Laboratory should perhaps be considered as a kind of Citizens' Assembly that looks back on the past."

Again, you're probably familiar with the idea of Citizens' Assemblies. They have been used in many countries nowadays, unfortunately not much in the UK. But, in fact, they may have been used in Northern Ireland; they certainly were used in the Republic of Ireland. Citizens' Assemblies have been used to try - and indeed, in the Republic, quite successfully - to develop collective agreement on highly controversial issues such as, in the context of the Republic of Ireland, abortion. Different groups, often seemingly opposed, are brought together, broadly representing citizens, and are involved over a period, often a few days, in discussions or debates facilitated by experts, guided by the agenda, the perspectives, the opinions of citizens who have been selected to take part in this exercise; and the results are often very positive - opposing viewpoints can at least reach a compromise, or a collective agreement on what to do about an issue such as abortion.

And I think a History Lab, in its best version, can be a bit like that - a conversation, a debate, a discussion between a wide range of citizens, advocacy groups, policy advisors at state, regional government or other levels, who may have very, very different perspectives, but who can come to some kind of shared agreement about the kinds of stories from the past that are relevant for the future, thanks in part to the facilitation by experts, who can help unblock discussions when they seem to be reaching an impasse. It won't always work.

It doesn't always work, but that would be my hope. So the discussions are facilitated by experts, but the outcome of the History Lab is not dictated by the prior knowledge of the experts. We, as experts, have to be open. I hope we are open to the possibility that the History Lab will generate results, generate stories that we didn't expect at the beginning of the process. But it's a big challenge and I wish you all the luck with the remaining time you have for this project!

"Citizens' Assemblies have been used to try to develop collective agreement on highly controversial issues. And I think a History Lab, in its best version, can be a bit like that - a conversation, a debate, a discussion between a wide range of citizens, advocacy groups, policy advisors at the state level, regional governments, or other levels, who may have very, very different perspectives, but who can come to some kind of shared agreement on the kinds of stories from the past that are relevant for the future, thanks in part to the facilitation done by experts, who can help unblock discussions when they seem to be reaching an impasse."

Have you had people bring different stories to the History Lab you promote?

Not really, because my only active participation in the History Lab is in the Transportation Department. ... Well, that's not entirely true. I've also conducted similar exercises with another specialized group, the Mobility Studies master's students. But in none of these groups did we really have the time to generate the kinds of discussions or debates that I've just described as ideal for a History Lab.

It's not possible to do what I put forward as the ideal in a three-hour session, which is the time I have for a History Lab at the Department for Transport (DfT). Sometimes Charles and I struggle to get the DfT to agree to three hours, because these people are expensive, the cost of their time goes up!

I also co-lead a network of workshops in the UK that sought to develop usable understanding of the past, and that some of the results of these workshops - I think we did three or four - they were published in a book that came out several years ago. These workshopsWe were really trying to define the parameters, the structures, let's say, for conducting history labs in the future. Then the funding ran out, and I partially retired, and the other people went their separate ways and did other things in their careers - and that's what I meant when I commented earlier that I was a bit disappointed, because I don't think the History Lab ideal has really taken root as a kind of "sustained practice" in the UK - which was one of the many reasons why I was very pleased to be invited to be a consultant on your project.

In a way it's an irony - why do you want to have someone as a consultant who hasn't actually managed to do what he advocates?! I advocate the broader, more ambitious form of the History Lab, and I think that's what you [Hi-BicLab] are trying to do; that's why I'm so pleased to be involved in this project, even though I'm several hundred miles away.

You may see it differently from your point of view, but from ours, as Hi-BicLab, it was quite successful.

I believe we have succeeded in achieving the more limited objectives we set for these specific History Labs. These labs work: we receive feedback - the state loves it feedback - and we had feedback really positive. In the UK, the History Policy Network, which aims to bring together academics, policy advisors, politicians, commentators, etc., has used the DfT's History Labs as one of the case studies of a successful practice.

So, without false modesty: I believe we have succeeded in this limited ambition, but what we haven't managed to do is go beyond that and develop a much more ambitious and comprehensive form of History Labs.

What similarities and differences do you see between the History Lab you facilitated and the History Lab we are developing at Hi-BicLab?

I think I've covered most of the points. I think it's important to reiterate that there is a shared commitment to learning from the past, returning to the fundamental theme that has guided this whole conversation: understanding how we got to the present and, again, opening our minds to different futures.

I believe this is the great similarity between what we have been doing and what you are trying to do in Lisbon. However, as I said, the difference is that we have been engaging with different types of groups. The participants in my workshops are much more homogeneous, they are policy advisors, or students, for example.

You are dealing with a much wider range of citizens, promoter groups and so on. In any case, my workshops have been limited and relatively short sessions. You have an ongoing program, which I believe is fundamental to the success of a History Lab. In my workshopsCharles and I are facilitators, but we also bring specialist knowledge as a package. And we don't invite participants to challenge our expertise.

In fact, what we say to them is: "We know this material and we will provide you with policy documents to work on". But, let's be clear, these documents have been carefully selected. They have been edited, so to speak, so that the participants have some chance of understanding the content in the two hours, or the time, they have to work on them. Whereas in a broader History Lab, like the one you're running, and, as I said before, yes, we bring specialist knowledge, but in a way we're inviting people not necessarily to challenge, but to complement, to add something to the specialist knowledge, to introduce new perspectives, to raise new concerns in the present, and therefore to challenge all of us, both specialist historians and citizen historians, to understand the past in different ways -perhaps more or less subtly-, to reflect on these current concerns. This doesn't really happen in the History Labs that I lead. Their aim is to carry out this 180-degree evaluation and analyze current practices in the light of what they have learned from the past. So your History Lab is much more ambitious, I believe, in terms of involvement and the work you set out to do.

About the project

O Hi-BicLab is an exploratory project funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (EXPL/FER-HFC/0847/2021), which aims to mobilize history to engage different audiences in identifying key social, cultural and technical factors that have shaped the mobility (and immobility) of people, broadening our repertoire of city pasts, working in an interdisciplinary approach and involving partners in the co-construction of knowledge about urban mobility through thinking in the long term. Therefore, by understanding that the past is not a monolith, but a space in which, from research, we can grasp more layers of what happened and question our perceptions of the past, the present and think about our alternatives for the future.